To celebrate the release of Muslim Preaching in the Middle East and Beyond: Historical and Contemporary Case Studies, editors Simon Stjernholm and Elisabeth Özdalga take us through five essential things you should know about Muslim preaching.

1. Synchronised sermons

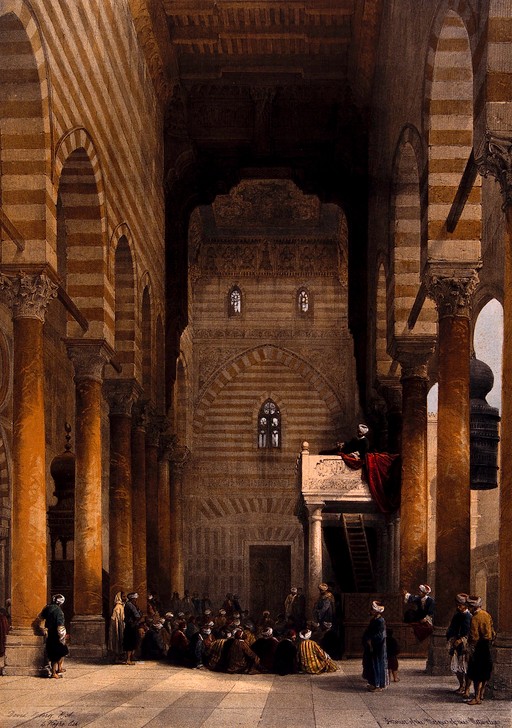

When a preacher, whether in a remote village or a global metropolis, climbs the minbar (pulpit) for the weekly Friday khutba, he joins a chorus of similar noon sermons, which rolls like a wave over the global time zones from Indonesia in the east to California in the west. What enables this remarkable unity in practice, tying hundreds of thousands of Muslim preachers together, is a common ritual, with roots in oratorical traditions going back to the days of the Prophet Muhammad – and possibly beyond.

2. Genres of Muslim preaching

Even if the khutba is the pearl among sermons, it represents just one of a multitude of genres of Muslim preaching. Also common is the waʿz, a freer form of preaching that can take place at any time and in many different settings, such as mosques, Sufi lodges, university campuses, street corners and coffee-houses. Less formal religiously instructive speech may also be part of a religious lesson (dars), a study group (halqa) or programmes organised on special occasions such as at a conference or in mass-media, like television and radio.

3. Preaching in your pocket

New media have revolutionised preaching practices, with respect to both preachers and audiences. Traditionally, Muslim preaching has taken place in a space where preacher and audience are physically face-to-face. In the contemporary world, preaching can be made available everywhere and anytime through various media. Listeners take part in oral religious messages gathered in front of the TV, alone while commuting, or in between daily chores. Access to Muslim preaching is now literally in almost everyone’s pocket and many preachers adapt their message to new forms of mediation.

4. Women preachers

Among Muslim preachers are women. Even though men have exclusively carried out most public speech, women also perform religiously instructive speech. With more equal opportunities in education and the expansion of the internet, women have increasingly claimed a space for themselves in public spaces. It is not sensational that women appear as waʿz or dars preachers in front of female audiences. Even societies with highly conservative gender-orders, such as Saudi Arabia, have a number of publicly known female Muslim ‘intellectual preachers’ who act in and through the semi-open spaces offered by the internet.

5. The role of the state

The emergence of the modern nation-state has had a considerable impact on the organisation of religious life, including Muslim preaching across the world. This is particularly evident in many states’ efforts to organise mosques and mosque administrations, educate imams and preachers, regulate the qualifications required to hold a khutba or a waʿz, and not least efforts to directly influence the contents of preaching through the production of state-sponsored, ready-made sermons. Especially this last point poses a challenge, as it risks increasing the distance between preacher and audience – a crucial relationship in order for preaching to be meaningful and effective.

About the authors

Simon Stjernholm is an Associate Professor in the Department of Cross-Cultural and Regional Studies at the University of Copenhagen.

Elisabeth Özdalga is a Professor and Senior Researcher at The Swedish Research Institute in Istanbul.

They are the co-editors of Muslim Preaching in the Middle East and Beyond: Historical and Contemporary Case Studies, available now from Edinburgh University Press.

[…] Read more from Elisabeth Özdalga: Five Essentials of Muslim Preaching. […]

MASHALLAH informative blog keep it up

The findings of the German Inaarah school casts doubt on the claim that there are “oratorical traditions going back to the days of the Prophet Mohammed” – so I understand at any rate.

Thank you for this insightful exploration of Muslim preaching! The dynamics and evolution of this practice are truly fascinating.