The past years have seen many commemorations in the Israeli–Arab conflict: 100 years since the Balfour Declaration (2017), seventy years since Israel was created (2018), fifty years since the 1967 war (2017), thirty years since the first intifada (2017), and twenty-five years since the Declaration of Principles (2018). In 2021, it will be fifty years since the EU’s Foreign Ministers issued their first declaration on the Israeli–Arab conflict and also fifty years since it started to fund UNRWA (The United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East). If not before, this should be an opportune moment for European policy-makers to reflect on the past half-century’s involvement of the European Union (EU) in the conflict – and the next fifty years.

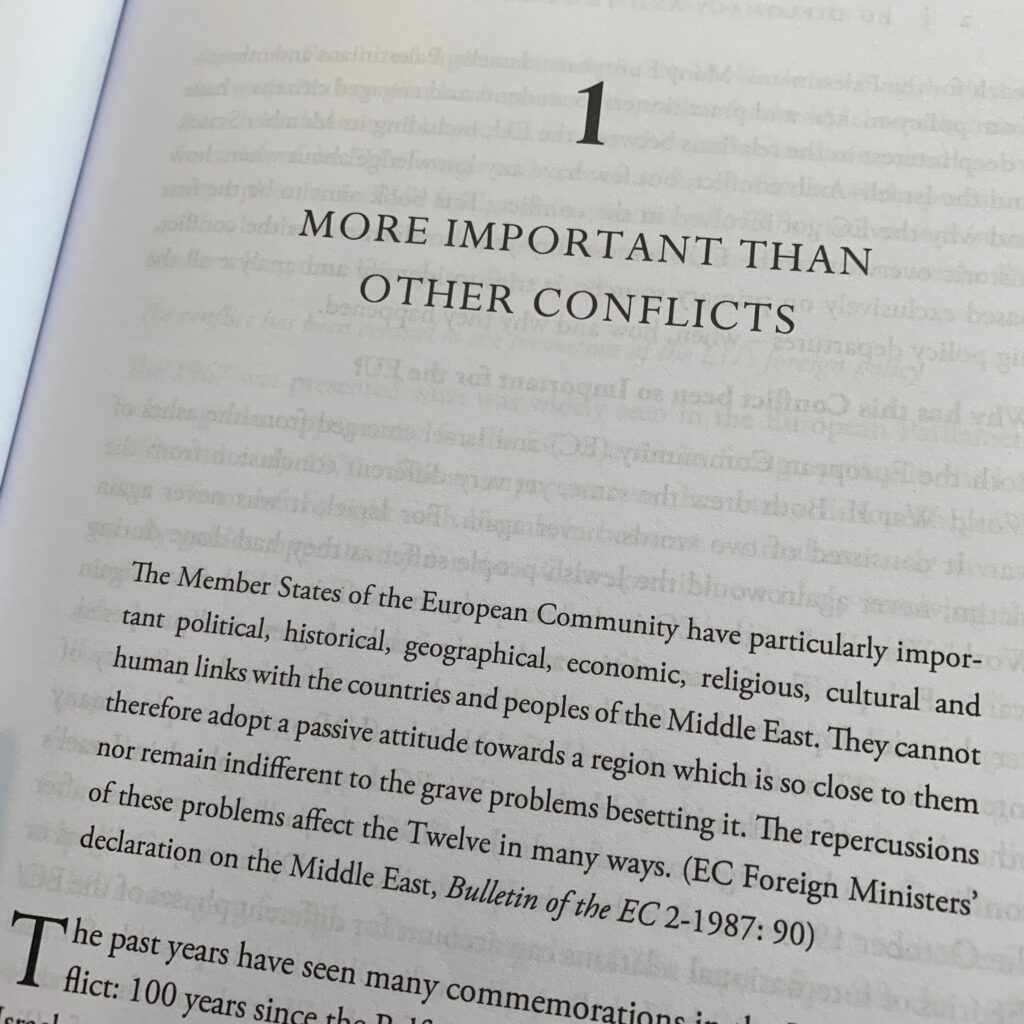

Many Europeans, Israelis, Palestinians and others – from policy-makers and practitioners to students and engaged citizens – have a deep interest in the relations between the EU, including its Member States, and the Israeli–Arab conflict, but few have any knowledge about when, how and why the EU got involved in the conflict. My new book EU Diplomacy and the Israeli–Arab Conflict, 1967–2019 (Edinburgh University Press, 2020) aims to be the first historic overview of the EU’s almost fifty-year involvement in the conflict, based exclusively on primary sources. The study covers over 70,000 pages of EU text and analyses 2,500 different EU statements related to the Israeli–Arab conflict in Bulletin of the European Communities/Union since 1967. Four broad arguments underlie the book’s overarching thesis that the Israeli–Arab conflict has been more important for the EU than other conflicts:

(1) The conflict has been central to the formation of the EU’s foreign policy

The 1967 war presented what was widely seen in the European Parliament to be a golden opportunity for what was then called the European Community (EC) to unite its foreign policy in the late 1960s and early 1970s. But as important was that many European politicians – from left to right with liberals in between – simultaneously saw an equally golden opportunity for the EC to contribute to help resolve the conflict. What emerged from the two golden opportunities was a widely shared twin belief that the Community could help the conflict to reach peace and that the conflict could help the Community to reach unity. Thus, the conflict became a test case for the EC’s emerging foreign policy during the 1970s, especially after the 1973 war. It was a test that the Community passed.

(2) The EU’s involvement in the conflict has been based on major strategic factors

The EU was much more dependent on oil from the Middle East than both of the superpowers during the Cold War. After the 1967 war, the Bulletin reported the EC depended for 80% of its oil consumption (48% of its total supply of power) on the Arab members of OPEC (the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries), a figure much higher at the time than both of the superpowers. This became an acute matter after the October 1973 war and the subsequent oil crisis, which had a shocking effect on the then nine Member States. The high oil prices led to massive transfers of wealth from the industrialized world to the oil producers in the Middle East, which in turn led to massive increases in trade, thereby creating another strategic objective.

(3) The conflict has had a persistent unique place in the EU’s foreign policy

The EU’s many hundred declarations and other statements related to the Israeli–Arab conflict are simply remarkable. Without having coded other conflicts, it is obvious through my quantitative and qualitative context analyses of the Bulletin that the Israeli–Arab conflict has received far more attention from the EU than other conflicts. There simply is no other conflict which has occupied such a central place in the EU’s foreign policy over these past five decades; no other conflict comes even close.

(4) The EU is part of the conflict

The EU’s long involvement in the conflict, its close political and economic ties with Israel, its massive economic support to the Palestinians, and its peacebuilding missions on the ground in the conflict have all contributed to make the EU part of the conflict. During the 1990s, third party involvement in the conflict was widely seen as necessary and beneficial to the Oslo peace process, which was meant to be a temporary, interim period, before a final peace agreement was to be reached. But the longer this process has lasted, the more it has been questioned.

The EU’s support for the Palestinian Authority and the peace process is now more and more seen, even by mainstream analysts, as helping Israel to uphold its illegal occupation rather than helping the Palestinians to achieve statehood. In the present era, there is a big risk that the EU will be an even bigger part of the conflict as the US scales back its support to the Palestinians, and the EU, including its Member States, steps up to help fill the holes left behind by the US.

About the author

Anders Persson is a political scientist at Linnaeus University, Sweden, specializing in EU-Israel/Palestine relations. His new book, EU Diplomacy and the Israeli-Arab Conflict, 1967–2019, has just been published by Edinburgh University Press. He can be found on Twitter at @82AndersPersson.