Richard Canning, co-editor of Brigid Brophy: Avant-Garde Writer, Critic, Activist speaks with Kate Levey, Brigid Brophy’s daughter, about her mother, her writing and her influence.

RC: Kate, we’re almost at the twenty-fifth anniversary of your mother Brigid Brophy’s death… but also a full 68 years since her publishing debut. Yet this is the first book dedicated to her legacy in its many forms. Why do you think we have had to wait so long?

KL: Firstly, let me say how proud I am that this book exists, and Richard, it is down to you that it does! It’s tough to raise the profile of Brophy, because she doesn’t fit any ready-made category, she was a genuine one-off. It could be said that she maintained her own public profile while she could, but has been rather out of fashion since the eighties. In fact her legacy is awesome, and she deserves better acknowledgement. I am grateful to each contributor to this collection of essays, for helping the Brophy revival.

RC: I think always of the sheer range of your mother’s interests, and the eclectic approach taken to style, genre, subject… We’re in an age where digital retailers don’t like this sort of unpredictability in writers, since they can’t argue: “If you liked that, you’d like {need to buy) this…”, which doesn’t help. That said, even in her day she was very very unusual in publishing books that all contrasted with each other as much as they had things in common…

KL: She certainly didn’t think much of writers who stuck to a formula, churning out the same kind of books year after year. The new EUP book has been edited to illustrate the wide scope of Brophy’s intellect. She was interested in a variety of cultural figures and topics; and she was uniquely gifted in being able to handle them all, in styles which suited her tastes. She wrote a children’s book, she wrote plays, campaign leaflets, novels and non-fiction, and never at any point got stuck in a rut. Each chapter in the EUP volume highlights a facet of Brophy’s talent. The book is a wonderful tribute to her.

RC: We’re bound to move on to the question of Gender at some point. Your mother was not only ahead of her time – she is probably ahead of the current moment, too! There have been attempts by feminists to appropriate her writing to a “woman’s fiction” tradition, or to “feminine writing” generally. Your mother was a feminist of course, of her own fashioning, but what do you think she would have made of a womanly canon?

KL: As an essay in the book discusses, Brophy was disinclined to align herself with any formal movement which she felt treated men as inferior. She certainly felt the barb of gender bias when her play The Burglar was judged harshly, and she wondered if a play by a man would have been better received. So she understood about the aims of feminism. But actually, Brigid Brophy’s personal canon would not be organised along gender lines but would more likely be ‘wonderful books regardless of the gender of their writers’.

RC: COVID-19 makes me think relentlessly of Brigid Brophy’s singular role as begetter of the Animal Rights movement. To me, the debates over the pandemic have missed a simple, obvious truth which I believe she would have been pointing towards: that COVID-19 is yet another zoonotic disease, originating in and entirely dependent upon slaughter practices in the meat industries. It’s spooky, if unrelated, how many flare-ups there now are in meat processing plants: not because meat per se is infected, but, oddly enough, because of the low temperatures and also the fact that the hygiene of the meat has been a priority, over and above sensible working conditions for employees… Your mother was firm and clear about her position on animal rights, brooking no compromise, where so many others did. Was she consistent, entirely, or do you think she also became more partisan or extreme as the key Animal Rights messages were not heard?

KL: Brophy’s role was exceptional: she placed animal rights in the public domain, where discussion of the topic had previously been an esoteric interest.

The catalyst was her article of 1965 which deliberately echoed Tom Paine’s Rights of Man; in it she argued that animals had the right not to be eaten. She changed from being vegetarian to being vegan in later life, which meant quite a restricted diet in the early days when vegan food was almost unheard of. Brophy deplored the move towards greater commercialisation of animal industries, because they intensified the exploitation of animals. Exploitation of human beings was equally indefensible, in her view.

RC: You’ve written several times now about your parents and your upbringing in very moving and personal terms. How do your own memories and feelings of Brophy and of Michael Levey, your father, coincide with the sort of things critics, activists and readers focus on?

KL: That’s a fantastic question! I think there’s a private Brigid Brophy quite distinct from the public persona she had. I believe it’s sometimes interesting for readers (and it might perhaps be of use to academics) to hear a different side of an author’s personality.

RC: On a related note, Jill Longmate in the book describes with great guile and care the art exhibition co-conceived by your mother and by the writer Maureen Duffy. You’re the owner of its only catalogue! As a child, were you encouraged by your parents to try out all of the arts – in practical as well as in receptive terms? Did you paint, sing, play and write?

KL: I had no talent for anything but enjoyed making things. I liked the sense of activity when the items for the Prop Art exhibition were being created at home. The polystyrene wig stands with their blank faces were being turned into witty and erudite discussion pieces by Brigid and Maureen, however, I insisted on being bought my own because I enjoyed decorating them with colourful sequins and adding extravagant hair and beads for eyes.

RC: The EUP book aims to give space to Brophy’s many types of book… I won’t restrict you to her fiction, then, but is there a single book of hers that you come back to more often than the others – that speaks to you? If so, which is it, and why?

KL: I think the EUP book rather encapsulates my ‘difficulty’: Brophy wrote so much that is poignant, that is important, and that is illuminating. I considered telling you it’s Flesh (1963) because Marcus is so like my father, then I thought, actually the article, The Rights of Animals from 1965 is just so honed and relevant, and I often re-read it. I will settle for The Snow Ball, in which my mother’s consummate prose suffuses a plot that reaches an almost musical peak.

RC: And where do you think a Brophy novice should begin? Imagine… any kind of reader! The reader, perhaps, that you’d most like to “convert”!

KL: I have quite often been asked that question. I usually advise people start with The King of a Rainy Country, because it has a funny and pacy story, but is also witty, elegiac, and wryly beautiful. As a route into Brophy, it’s perfect in my view.

Kate Levey is the only child of Brigid Brophy and Michael Levey. She writes about her parents and is dedicated to ensuring Brigid Brophy’s legacy is not forgotten. Now a grandmother of three, she lives in Lincolnshire.

Richard Canning is author or editor of nine books and is presently Visiting Professorial Research Fellow at the University of Buckingham. He has specialised in twentieth-century LGBTQ literature, and his critical life of Ronald Firbank is forthcoming from Harvard University Press.

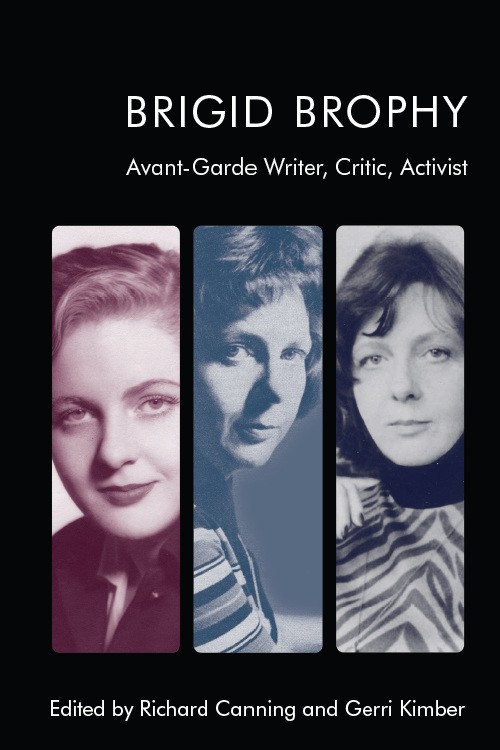

Brigid Brophy: Avant-Garde Writer, Critic, Activist edited by Richard Canning and Gerri Kimber is published by Edinburgh University Press.