By Andrew DJ Shield, University of Leiden

Queer Freud Today

At an all-gay dinner last month, a friend – trained biologist, amateur astrologist, and psychoanalytic dilettante – shifted the dinner conversation to his playful diagnosis of the dinner guests’ stages of psychosexual development: “You’re orally fixated…” he explained to one loquacious guest, before turning to another: “And you’re anal expulsive.” Everyone listened with amused grins, and welcomed the cursory analysis. Oh, and this was complemented with the star charts he pulled up on an app on his iPhone. This made me wonder: How is it that Freudian concepts continue to resonate in 2020, including with queers? Certainly this was not inevitable.

Queering Freud Differently, the newest special issue of Psychoanalysis and History, shows how radical psychoanalysts challenged the homophobic status quo of the psychoanalytic profession in the 1970s and 1980s. Dagmar Herzog – renowned historian of psychiatry and psychoanalysis, sexuality, and modern Europe – edited and introduces the special issue, which is composed of personal reflections, theoretical inquiries, an illustrative mind map and primary documents (e.g. personal correspondences annotated by Herzog). No need for mastery of psychoanalytic jargon: the audience for this issue should include everyone interested in the history of sexuality.

Who rescued Freud?

Two names are central to this special issue: (U.S. American) Robert Stoller (1924–91) and (Swiss) Fritz Morgenthaler (1919–84). Stoller’s speech at the American Psychiatric Association’s meeting in May 1973 “lent indispensable aid to the project of formally removing homosexuality from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM) in November of that same year” (Herzog, 2; all citations from this issue). Morgenthaler was the “very first European analyst, since Freud, to assert directly, without any caveat or circumlocution, that same-sex desire was not, indeed never, a pathology” (Herzog, 2).

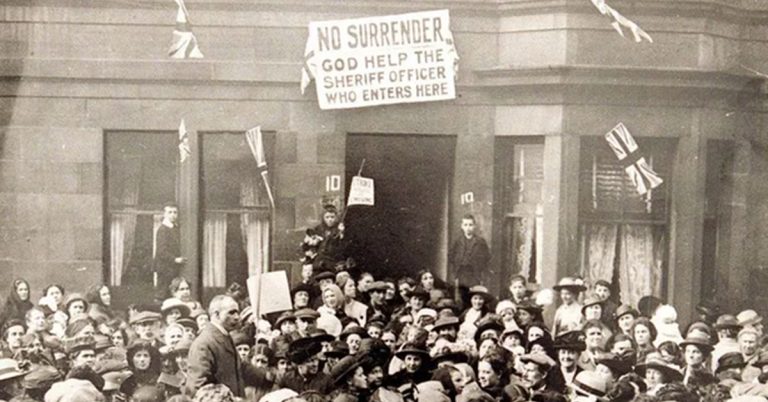

In an era when protest and transformative change often came from outside of the establishment, Stoller and Morgenthaler used their positions as medical professionals to effect change from within. Stoller, for example, skillfully used the homophobic jargon of his contemporaries to lampoon their analyses of homosexuality. Thus Stoller described his heterosexual “cousin George” who – by some analysts’ professional standards – could only be diagnosed as a “latent homosexual”; after all, he was

… rather boastful about his erotic prowess, inclined to drink too much when socially ill at ease, given to telling jokes about queers, smokes big cigars, regularly plays poker with his male friends, and wastes weekends watching football on TV… He has too many flaws; his homosexuality just oozes out of him. (You might almost say it is what makes him heterosexual)

(Stoller, 1985; quoted in Herzog, 10 fn. 6)

Neither Stoller nor Morgenthaler was a queer hero from the get-go. In the 1960s, both published works with homophobic and transphobic prejudices. The special issue does not ignore these problematic starting points. The article of Aaron Lahl and Patrick Henze interrogates Morgenthaler’s early, pathologizing texts; yet as Herzog argues, it is precisely for these reasons that “the transformations of both men – ahead of the rest of their profession [is] so intriguing” (Herzog, 4).

Queering Psychoanalysis: About the Issue

Part biography, part intellectual history, the articles and documents in this special issue achieve two results. First, the reader gets to know Stoller and Morgenthaler – who they read, who were in their social circles; second, the reader dives into the ideological debates and theories these radical psychoanalysts advanced within their profession.

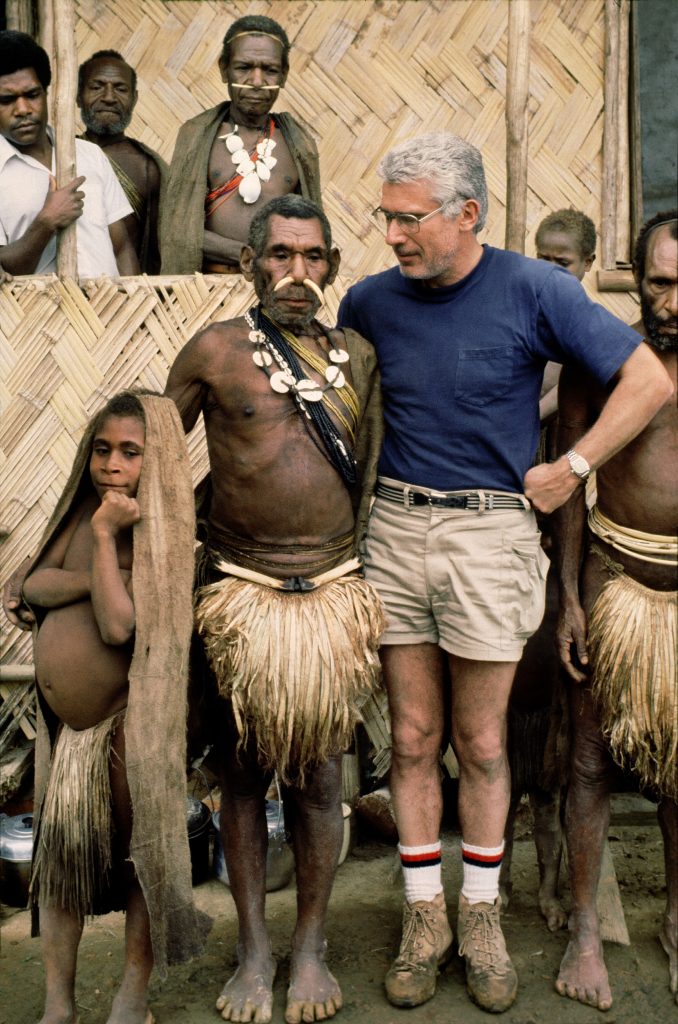

Anthropologist Gilbert Herdt’s article – on Stoller’s work with transgender variance, sexual excitement, and village dynamics – immediately drew my attention, as Herdt’s anthology Third Sex, Third Gender (1994) was foundational during my graduate studies of sexuality and gender.

Herdt initially contacted Stoller, who became his mentor, in the 1970s: “At the time, I was reaching out to a few scholars in search of wisdom in understanding the remarkable cult of boy insemination practices I had discovered among the Sambia people” (Herdt, 15). On a personal level, Herdt recalls the support Stoller provided him during a time when “de facto heteronormativity was the norm” and when it was relatively unprecedented for senior scholars to support LGBTQ professionals and their queer research (Herdt, 18).

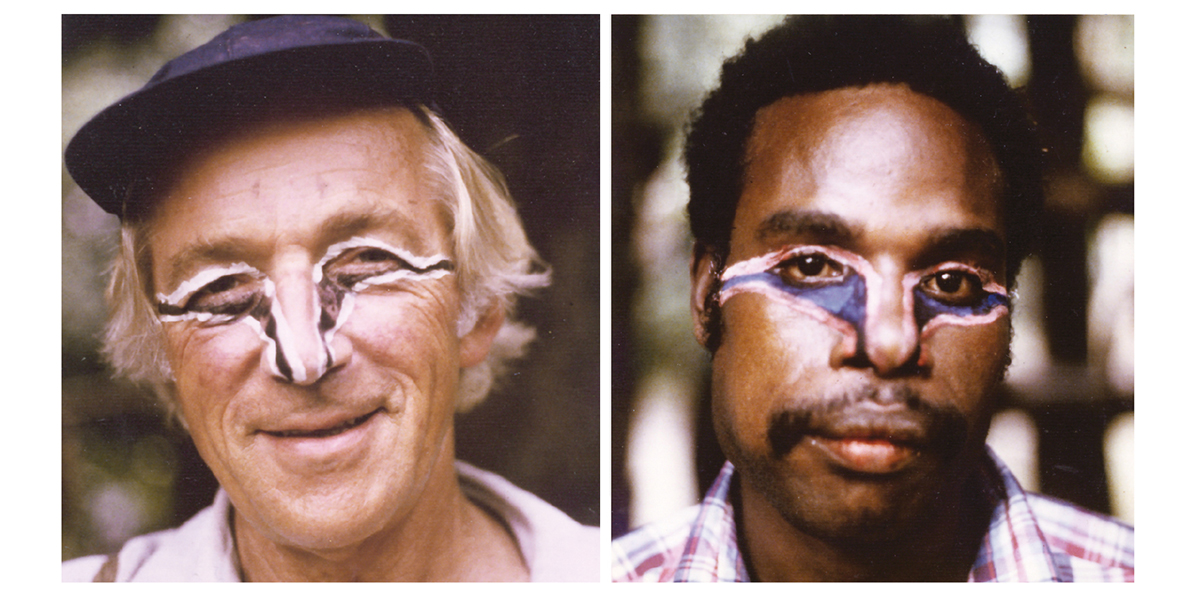

Stoller too conducted ethnographic work on sexual excitement in Papua New Guinea. And interestingly, Morgenthaler also traveled there in the 1970s in order to theorize gender identity development and the universal potential (or lack thereof) of the Oedipus complex. Stoller’s and Morgenthaler’s radical ethnographic methods – “ethnopsychoanalysis” – were central to their ability to think broadly about human nature and societal influences on sexuality and gender.

Next, Jeffrey Escoffier’s article contextualizes Stoller’s work within the history of pornography. He sparked my interest from the start, ruminating on what Stoller would have thought about Pornhub (i.e. as a rich source of empirical material). Escoffier – whom I admire for works like Sexual Revolution (2003) and Bigger Than Life: The History of Gay Porn Cinema from Beefcake to Hardcore (2009) – interweaves the history of mass porn production with Stoller’s theories of sexual excitement, drama, and scripts, drawing also from Stoller’s ethnographic research on/with members of the porn industry in the 1980s.

The issue ends with ruminations on how Morgenthaler’s understandings of sexuality compare and contrast with Foucault’s (see document by psychiatrist Martin Heinze), and with Lacan’s (see article by psychoanalyst Ulrike Körbitz).

Herzog’s introduction is open-access, and the special issue complements Herzog’s recent monograph Cold War Freud (2017), and her edition of Morgenthaler’s On the Dialectics of Psychoanalytic Practice (2020).

Did Freud ever die?

My mother, who was studying human development in the U.S. in the 1970s, remembered the attitude toward Freudian theories as “behind the times, out of touch,” and only potentially relevant when contrasted with humanistic psychology or other “positive approaches,” including those that emerged alongside youth counter-cultures. (For example, the idea that one could “expand one’s universe” through meditation was trending, along with the general belief that one could develop one’s “sense of self” creatively.) Feminists alleged that Freud was obsessed with and exploited women, and that his rigid interpretations were framed by the Victorian era. To most non-psychoanalytic psychologists, feminists, and queers, there was little to celebrate in Freud.

But what few outside of the profession realized at the time was that radical analysts were advancing new anti-homophobic interpretations of Freudian theories. These theories would have lasting effects on the intellectual legacies of psychoanalysis and the continued struggles for LGBTQ rights.

Overall, the special issue shows how Stoller, Morgenthaler, and those in their intellectual circles, rescued the Freudian theories that had been hijacked by conservative and homophobic professionals. In this way, they allowed a new generation – including many queers – to see the radical potential in Freudian psychoanalysis.

Andrew DJ Shield is Assistant Professor of Migration History at Leiden University. He is the author of Immigrants in the Sexual Revolution: Perceptions and Participation in Northwest Europe (2017) and Immigrants on Grindr: Race, Sexuality and Belonging Online (2019), and has recently published articles in History Workshop Journal, Sexualities, and Clio. Femmes, genre, histoire.

The special issue of Psychoanalysis and History, Queering Freud Differently: Radical Psychoanalysis and Ethnography in the 1970s-1980s is out now. You can read the introductory article by Dagmar Herzog for free until August 2020. Find out how to subscribe to the journal, or recommend to your library.