The idea of the death-wish has haunted the history of psychoanalysis in its encounters with cognitive disability. But who is wishing death on whom? This is one of the questions arising from ‘Psychoanalysis Confronts Cognitive Disability’, the intriguing recent special issue of Psychoanalysis and History edited by Dagmar Herzog.[1]

The ‘talking cure’ has always struggled with the cognitively disabled mind. If the key to realisation lies in the dynamic verbal interaction between the subject and the analyst, what does psychoanalysis do when confronted by a non-verbal, or verbally limited, human, appearing to lack an inner life?

The cognitively disabled mind has resolutely failed to offer up the stories psychoanalysis craves. These are narratives of transition, self-realisation, cathartic insights, and intriguing reveals. Like any good detective story they take us up several blind alleys before revealing the solution to a mystery, pulling the explanatory rabbit from the mental hat of the subject’s mind.

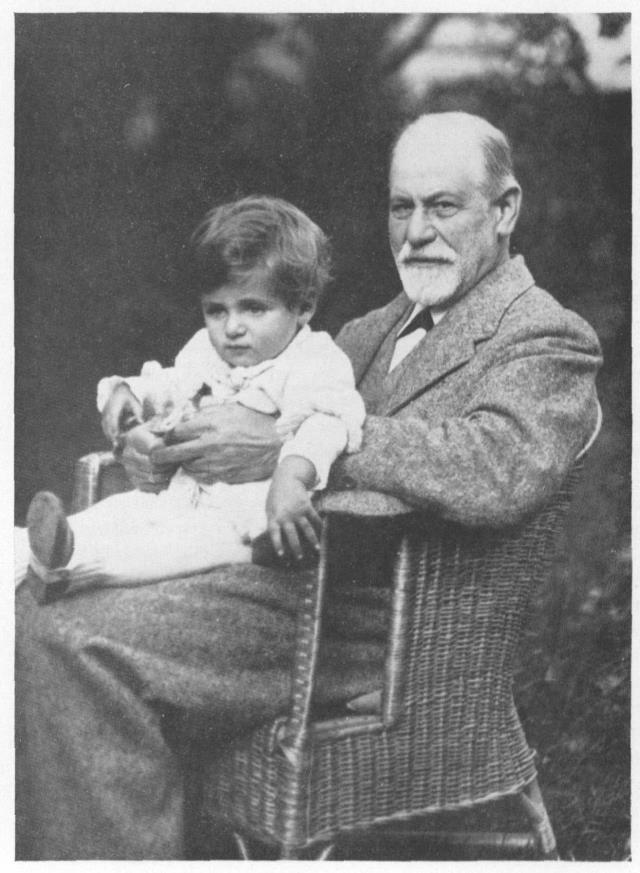

Think of Little Hans, Dora, Rat man and Wolf man, to take the most obvious examples, the puzzling but ultimately solvable mysteries with which Freud launched a genre of psychoanalytic story telling.

The problem with cognitive disability, for the Freudians and many of their successors, was that it lacked mystique and exoticism. It was barren and unchanging, and a good story could not be extracted from a vacuum. It is for this reason, as Dagmar Herzog points out, that through to the late twentieth century psychoanalysis ‘vacillated between indifference and disdain or unthinking derogation’ for the cognitively disabled subject or, as they saw it, non-subject.[2]

Attention turned to the parents. Surely, the psychoanalysts concluded, they could only wish for the death of such children? And surely they must mourn for the normal child they had dreamed of, who never arrived? So the idea of the parental death-wish was born, at last a compelling story that could be mined, if only by proxy, from the empty minds of the cognitively disabled.

But it was nothing new. The changeling myth had medieval origins: mischievous sprites stealing the unwatched human baby from their cot, and replacing it with a terrifying, grinning, brainless imitation of a human from the spirit world. The parents must endure guilt and grief for the child they have lost, but also suffer a life of pain and misery caring for the non-child they have acquired.

To this day, well-meaning social workers tell parents of a cognitively disabled child to grieve first for the loss of the child they hoped for, and then prepare to cope with the different sort of child they have been given. Cognitive disability is a tragedy, a living death, a blight on the lives of the cognitively typical.

Which leads us to genetic counselling. This, as Marion Schmidt’s fascinating account in this issue testifies,[3] is aseemingly benign and helpful descendant of eugenic science offering the opportunity to anticipate and prevent birth defects. However, it holds within it the psychoanalytic idea of the death-wish against a cognitively disabled child.

A debate now rages over, for example, antenatal testing for Down syndrome – does it offer prospective parents the option to eliminate a disease, or a type of human?

A person with Down syndrome, someone with a third copy of Trisomy 21, is destined to be the person they are from the moment of conception. A child without the extra chromosome hasn’t died to make way for a different child. This person was always going to be this person.

So, we must ask, has psychoanalysis simply given its own form of scientific authority to an enduring myth that demonises cognitive disability? Does the idea of the parental death wish reflect not so much the wishes of parents but, as Herzog puts it, ‘the hostile and rejecting feelings… of many psychoanalysts themselves’[4], repelled when confronted by a form of human they do not wish to acknowledge within the category of person?

Those within psychoanalysis who have argued that a cognitively disabled mind is a human mind warranting respect and attention have often fought, and still fight, a lonely and isolated battle, as this issue of the journal testifies. Perhaps it is time for many in the profession to gaze into the mirror, and ask themselves where the death-wish truly lies.

By Simon Jarrett

Simon Jarrett is an honorary research fellow and former Wellcome Fellow at Birkbeck, University of London. His book on the history of idiocy from 1700 to the present day will be published by Reaktion Books in 2020.

[1] Psychoanalysis and History 21:2 (2019) Special Issue : ‘Psychoanalysis Confronts Cognitive Disability’

[2] Dagmar Herzog, ‘Psychoanalysis Confronts Cognitive Disability’, p, 136

[3] Marion Schmidt, ‘Birth Fefects, Family Dynamics, and Mourning Loss: Psychoanalysis, Genetic Counseling, and Disability, 1950-80’, pp. 147-169

[4] Herzog, ‘Psychoanalysis Confronts’, p. 138

We hope you enjoyed reading our blog post about cognitive disability and its psychoanalytic discontents. Leave a comment below, and find out more about Psychoanlaysis and History and how to subscribe.

This article challenges deep-seated biases in psychoanalysis towards cognitive disability. It critiques how psychoanalytic narratives have historically dismissed these individuals’ inner lives, perpetuating harmful myths rather than understanding and respecting their humanity. An important call for introspection within the field.

#aurahomes #cerebral palsy therapies #occupational therapy treatment for autism #applied behavior analysis aba therapist #special educator for autism #autism therapies#aurahomes #cerebral palsy therapies #occupational therapy treatment for autism #applied behavior analysis aba therapist #special educator for autism #autism therapies