Tell us a bit about your book

Queens, Eunuchs and Concubines in Islamic History, 661–1257 is the first comprehensive study of sexual politics in medieval Islamic history. While there are several books written on the Ottomans and Safavids, we do lack studies exploring how women lived in the medieval period. My work discusses the political role of women, in and outside the harem, and explores how gendered politics developed, particularly with the help of their best allies, eunuchs. There are various questions I aim to address:

- Why were women prohibited from education when schools were established?

- Unlike in Byzantine or French societies, why did women who had the ability and authority to document their thoughts, religious interpretations and memoires, never attempt to do so?

- Why did Saladin, the legendary commander during the Crusades, count on his deputy, a eunuch called Qaraqush – and why were half of his army at times formed of eunuch warriors?

- Why didn’t Muslim queens (Shi‘i and Sunni alike) fight for their own gender when they came into power?

What inspired you to research this area?

The majority of studies during the last two decades, despite bearing titles like ‘women and gender in Islam‘, have in fact focused primarily on the religious dimensions of Islamic law, such as the veil, divorce, equality and patriarchal readings and interpretations of the Qur’an. The majority of such studies contain a limited chapter on women in early Islamic history, and then they move to feminist movements in the so-called Arab and Islamic world. Largely missing from these studies are the many rich sources and historical documents that discuss the socio-political, religious and even military role of women and their entourages of eunuchs and atabegs (father –regent) in an area extending from Iran and Central Asia to North Africa. To address the wider and more complex context, and redress this gap in the literature, I aim to shed more light on the contribution of women in medieval Islam – particularly important in contemporary times as women still face huge obstacles to positions of power and recognition.

What was the most exciting thing about this project for you?

Discovering how Islamic history developed in reality, rather than according to religious domination and interpretations. Unravelling a huge amount of material in sources and documents, which covers the influential phenomenon of eunuchs as a third gender, and their impact on sociology of Islamic history; in addition to their perplexed relations with the harem in a holy pact for political interests. Also, the diverse ethnicities under medieval Islam worked differently according to pre-Islamic influence. While the early Arab Muslims tried to act according to their conservative way toward women, we also have Indians, Persians, Turkmens and Mamluk–Egyptians who introduced queens.

Did you discover anything particularly strange or surprising?

There were many cases and situations. One that comes to mind is the case of the scholar and da‘i-preacher in Yemen, contemporary to queen Arwa. He didn’t mind a female coming to power, but he wasn’t happy with her appointment by the caliph as hujja (supreme religious authority after the caliph). In order to find a convincing way to defend the caliph’s decision, al-Khattab wrote this misogynous fantasy: ‘The human bodily qumus (shirts) are not vitally important and are not the real indication of a person’s gender, but the deeds, which generated from their souls’. Therefore, Arwa is a male in women’s body, like great women of the prophet (Khadija his wife and Fatima his daughter). He goes on to say: ‘If a woman appears in a female shirt, yet achieved good appraisable deeds, she is actually a male enveloped in female body. On the other hand, if a male appears in a male shirt and shows no merits; in this case, he is definitely a female’. It is very strange and surprising that this first queen, who reigned for two decades as queen-regent and four decades as sole sovereign queen, did not encourage her own gender to participate in political life, including her own daughters. She did not use women as advisors or assistants and continued the male habit of putting men forward.

Did you get exclusive access to any new or hard-to-find sources?

Yes, there have been many sources that I’ve been able to access which bring a better understanding of the age and challenge previous misconceptions. In the Cairo national archive, I found the manuscript of a leading 15th century chronicler al-Suyuti on eunuchs in Islamic law.

In the Indian archive in Mumbai, I had access to the manuscript of chief Isma‘ili preacher, ‘Imad al-Din Idris, which provides details of the first queen in Islam – Arwa of Yemen who ruled 1098-1138. Also in the Indian archive is the Fatimid caliph, al-Mustansir documents or epistles. This is unique as it contains official correspondence between several queens – one of the only cases in Islamic history, to the best of my knowledge.

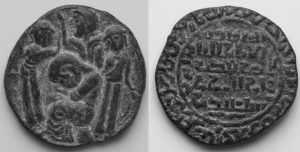

In addition, there was the hard to find coin of queen Tamar of Georgia (1184-1213) with her writing in Arabic (queen of queens) that encouraged and influenced Muslim dynasties to follow. After the death of Saladin in 1193, we see a coin featuring four women mourning him. Bearing in mind that human figures were prohibited in Islamic art, producing a coin with four women to circulate around what is today Syria and Eastern Turkey was controversial – like a twitter storm of the age. Lastly, there was the rare dinar of Muslim queen Abish of Shiraz in Iran in the late 13th century.

Did your research take you to any unexpected places or unusual situations?

In one of my trips to Algeria, I was surprised to see a large statue of the Berber-Amazigh queen of North Africa, Dehia, or better known as Kahena in the Aures city of Khenchela. She courageously led the military resistance against the early Arab Muslim conquests for decades, until she died in 704. The majority Muslim country of Algeria still commemorates her legacy and are proud to highlight her gender by making this statue.

Has your research in this area changed the way you see the world today?

Definitely. We see several examples through history of free or former slave women who lead, ruled and commanded armies – in no way less equal than men. Yet in the world today, we are confronted with various misogynistic movements, such as ISIS and Boko Haram in West Africa, Libya, Syria, and Iraq and the Taliban in Afghanistan. All of these movements have declared a new caliphate, enslaved women and sold them in the market, deprived them of education at any age and forced them to cover their bodies fully. By comparison, medieval models of female rule have been revived in Muslim countries such as Pakistan and Bangladesh and also, one can understand why the Kurdish women in Syria and Iraq are not only accepted in politics, but respected as front line soldiers against Isis – they are the great granddaughters of the 13th century Kurdish Ayyubid queens.

What’s next for you?

Volume two of this book! I aim to cover the gender and politics in Islamic history under the dynasties of North Africa (Maghreb), Spain, The Mamluks, Mongol and Safavid Iran, and Saljuqs of Anatolia and early Ottomans.

In addition, I’ll be working on a book exploring how chroniclers, scholars and politicians looked at women by translating their primary source texts. Comments will enrich the translation with explanations, comparisons and annotations.

Queens, Eunuchs and Concubines in Islamic History, 661–1257 is available now in the Edinburgh Studies in Classical Islamic History and Culture series.

Taef El-Azhari is Professor of Islamic and Middle Eastern History at the University of Helwan, Egypt. He received his doctorate in Middle Eastern history from the University of Manchester. His interests, both in research and teaching, focus principally on Turkmen-Kurdish social-political history and the Crusades. His most recent books include Zengi and the Muslim Response to the Crusades and The Saljuqs of Syria during the Crusades.