Distributed cognition – the idea that cognition or the mind extends across brain, body and world – is not a term that rolls off the tongue. Nevertheless, distributed cognition describes a fundamental aspect of being human.

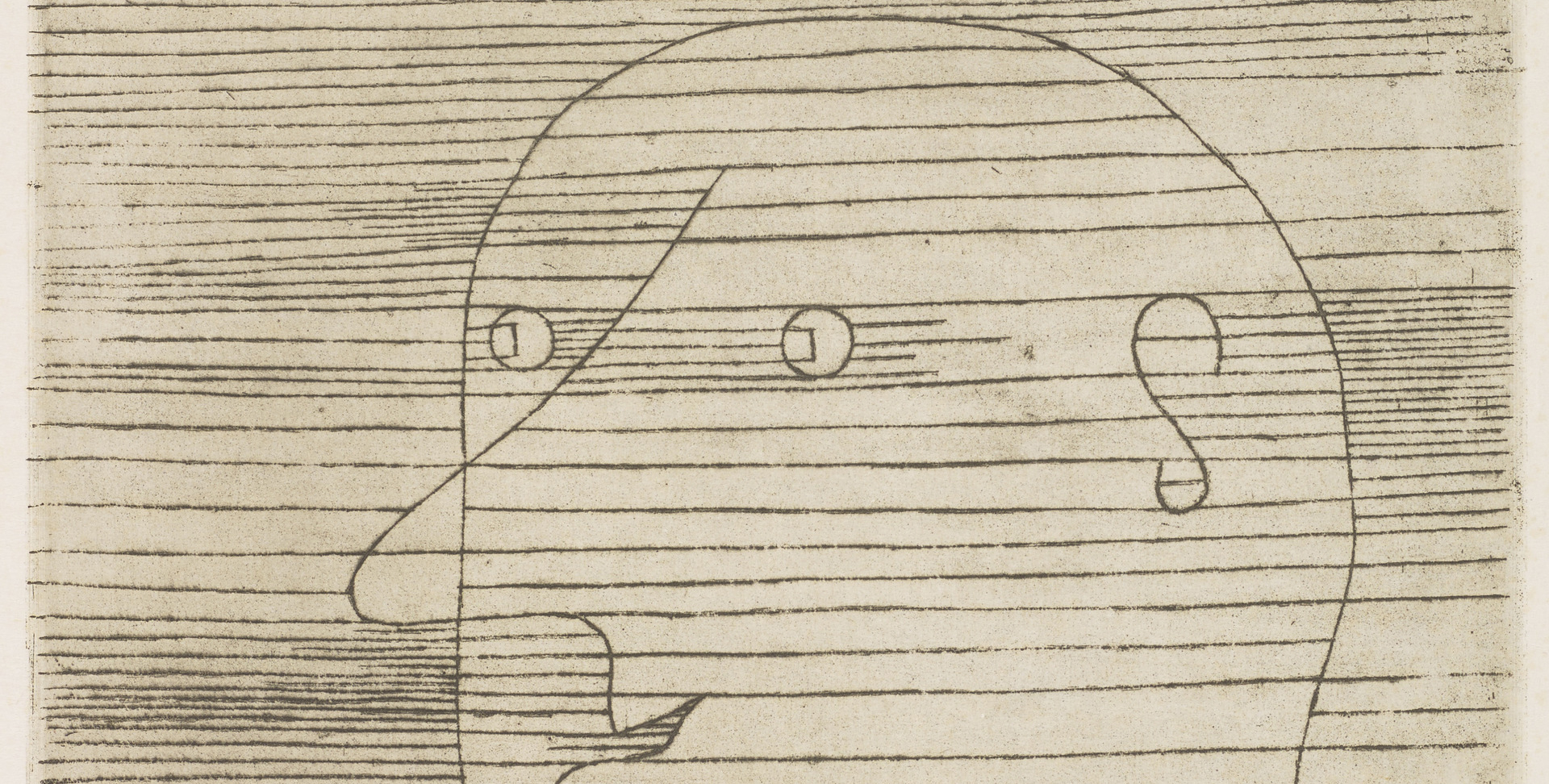

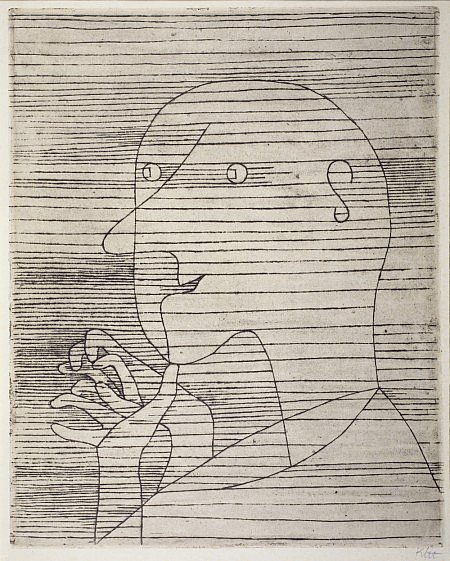

Examples of distributed cognition are everywhere. For instance, the painting ‘Rechnender Greis’ (‘Old Man Calculating’) by Paul Klee shows a man counting on his fingers. He is using his body to extend his mind’s capacities.

More recently, philosophy and cognitive science have been drawing their examples from technology. For instance, David Chalmers claims that his iPhone is part of his mind. By storing and providing access to information, it relieves the burden on his biological memory. By figuring out sums, it offloads calculations previously done inside his head.

4E cognition: embodied, embedded, extended, enactive

Distributed cognition is also known as ‘4E cognition’, because it encompasses:

- Embodied cognition: psychological states and processes are routinely shaped, in fundamental ways, by non-neural bodily factors such as bodily forms and movements.

- Embedded cognition: external resources (such as tools and technology) act as noncognitive aids to an internal thinking system located in the brain.

- Extended cognition: a coupled system of external resources, bodily movements and in-the-head processing constitutes the thinking agent.

- Enactive cognition: cognition unfolds (is ‘enacted’) in looping sensorimotor interactions between the agent and their environment, implying a close relationship between perception and action.

All four Es feature a social dimension. This is because thought and experience often depend on the external ‘resources’ provided by other people, social structures and cultural institutions.

Distributed cognition across the ages

One of the most interesting things to come out of the series has been the sheer diversity of how distributed cognition has been expressed (or suppressed), from the classical period to the 20th century.

Ancient Romans thought you knew what your slaves knew because you owned them – the classical equivalent of iPhones.

Renaissance man Robert Hooke described writing, like the brain itself, as a ‘repository’ that aids individual and collective thinking.

The socialite Lady Emma Hamilton thought that the best way to experience an ancient Greek mindset was to physically imitate poses on ancient Greek vases.

The Edinburgh History of Distributed Cognition comes at the very moment when modern-day technological innovations reveal the extent to which cognition is not all in our heads. Just as humans have always relied on bodily and external resources, so we have always developed theories, models and metaphors to make sense of the ways our minds extend across brain, body and world.

By Miranda Anderson, Douglas Cairns, Mark Sprevak and Michael Wheeler.

Miranda Anderson is an Anniversary Fellow at the University of Stirling and an Honorary Fellow at the University of Edinburgh. Her research focuses on cognitive approaches to literature and culture. She is the author of The Renaissance Extended Mind (Palgrave Macmillan, 2015).

Douglas Cairns is Professor of Classics in the University of Edinburgh. He has published widely on Greek literature, society and thought, especially the emotions. He is the author of Sophocles: Antigone (Bloomsbury Academic, 2016), Bacchylides: Five Epinician Odes (Francis Cairns, 2010), and Aidôs: The Psychology and Ethics of Honour and Shame in Ancient Greek Literature (OUP, 1993).

Mark Sprevak is Senior Lecturer in Philosophy at the University of Edinburgh. His research focuses on distributed cognition and computational models of the mind. He is the co-editor of The Routledge Handbook to the Computational Mind (Routledge, 2018), The Turing Guide: Life, Work, Legacy (OUP, 2017) and New Waves in Philosophy of Mind (Palgrave Macmillan, 2014).

Michael Wheeler is Professor of Philosophy at the University of Stirling. He is the author of Reconstructing the Cognitive World: The Next Step (MIT, 2005). He is co-editor of Heidegger and Cognitive Science (Palgrave, 2012) and The Mechanical Mind in History (MIT, 2008).

The Edinburgh History of Distributed Cognition

Cognitive science is finding increasing evidence that cognition is distributed across brain, body and world. The Edinburgh History of Distributed Cognition calls for a reappraisal of historical concepts of cognition in light of these findings. It engages with recent debates about the various strong or weak models of distributed cognition and brings them into discourse with research in the humanities. Together, the books in this series give a wide-ranging examination of the parallels (and divergences) from these models in cultural, philosophical and scientific works, from antiquity to the mid-20th century.

The History of Distributed Cognition project was generously funded by the AHRC. further resources are available on the project website: www.hdc.ed.ac.uk. The authors are also grateful to the AHRC for funding ‘The Extended Mind’ exhibition in a new collaboration with Talbot Rice Gallery, which runs from October 2019 to January 2020.