John Pollock’s new article on the true provenance of ‘Mr Shuckspr’se Box’ begins with an auction, although true to our ‘advanced age’, it is a live webcast auction. Our author bids on ‘A 17TH CENTURY IRON STRONG BOX’ and wins it; but he tells us, ‘quite what it is remains unclear’. The item is indeed no ordinary eBay fodder. The little black chest, its strap work and scroll ornament rusted with age, could have been hauled up from some long-forgotten treasure trove, and glowers out from the photographs, as if daring the onlooker to pick its lock. The central intrigue, however, lies with the letters inscribed into the steel lock plate, which swirl haphazardly across the top and bottom of its intricate fretwork and seem to announce the identity of its owner(s). Two initials – W. and S. – that, according to the antique dealer, are purportedly those of William Shakespeare, and a dated signature: ‘Ben 1600 Jonson’.

In this article, Pollock considers whether it could have possibly belonged to one or both of the two famed Renaissance poets, and attempts to unlock the mysteries of the black box, which, he discovers, is ‘designed to deceive’. Its elaborate locking mechanism, which boasts a false lock and concealed real lock, indeed seems to allude to the impossibility of discovering its secrets. Nonetheless, Pollock embarks on an investigative journey to discover the provenance of the box, probing the available evidence and consulting droves of experts in everything from handwriting to ‘heritage science’. The early part of the inquiry unfolds rather like an episode of the BBC series Fake or Fortune?, and will speak to those with an interest in antiquarianism:

“Had someone else got carried away, too, and inflated those really rather common initials to their highest possible apogee? Antique dealers at that, eh? […] Or could this be an orally transmitted familial provenance – the kind of private legend that cascades down generations, sometimes to a surprising degree? If so, then why hadn’t it gone public, and been offered as such, at Christie’s or Sotheby’s? After all, in our “advanced” age, just how hard could it be to stand up such provenance?”

This study will appeal to antique enthusiasts, then, but it will also have a considerable draw for Jonson and Shakespeare specialists. Pollock develops his analysis with forensic precision, and comes up with extraordinary evidence to support and call into question the extraordinary claims made about the box.

However, Pollock is also a master storyteller: his anecdotes bring the tale of the box to life, and his clever rhetorical flourishes animate the twists and turns of the investigation. Just when you feel you are beginning to get a sense of how to sort the box ‘facts’ from box ‘fiction’, Pollock reveals there are further mysteries inscribed into the metal chest:

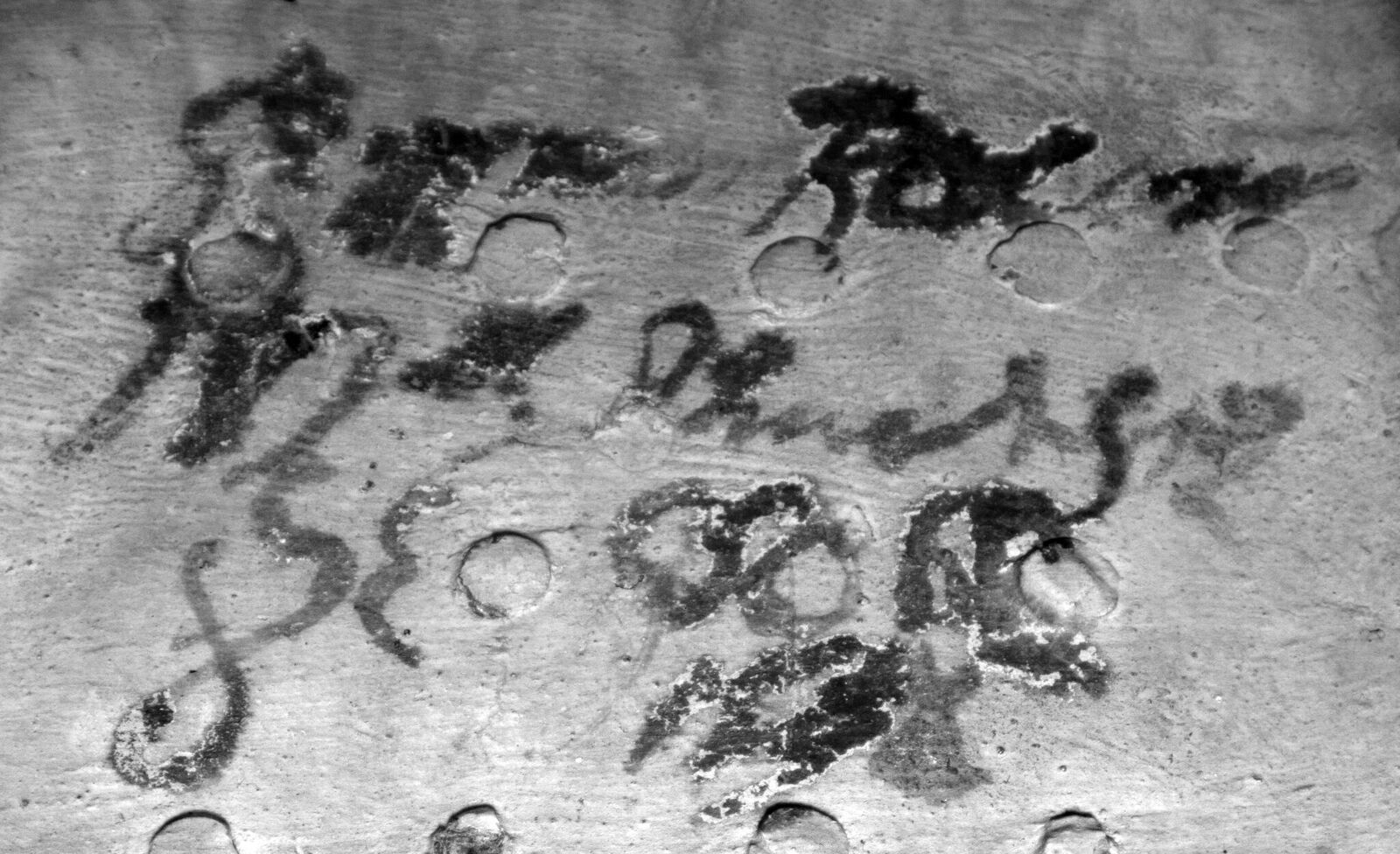

“In addition to the scratches and pricked “characterie” on the lock plate: divers scrawlings, heavily degraded, on three of its inside walls (perhaps where iron gall ink has engaged in a long, slow intimacy with iron oxide paint, before spreading and fading back into the skin of the box, like an ancient tattoo).”

Though some of these ‘mute Hieroglyphicks’ and ‘maddening squiggles’ are left shrouded in mystery, Pollock offers some hard-won expertise and provisional conclusions in a manner that will satisfy both believer and sceptic, teasing the legitimacy of the autographs and the notion of a possible forgery almost in the same breath. That he is actually able to provide answers to some of the questions he asks at the outset attests to the academic rigour and patience of his investigation.

The ‘Shakespeare Box’ constitutes a kind of black hole from which no one has emerged to tell its story, until now. The lively and immersive study offered by Pollock will leave readers wondering about the truth of the little black box long after they have examined its crude engravings and glimpsed its secrets. ‘Instead of being “too good to be true”, could it, in fact, be “too bad to be false”?’

Keep an eye out for the article, published in November.

About Rebecca Newby

Rebecca Newby is a third-year doctoral candidate working in English and French medieval studies in the School of English, Communication and Philosophy at Cardiff University. She is currently researching the construction and reception of endings in medieval romance and teaches undergraduate literature modules. She has an article in the current issue of Arthurian Literature, entitled ‘Illusory Ends in Chrétien de Troyes’ Erec et Enide‘ and a forthcoming chapter in Medieval Insular Romance Made New: Translation and Transformation due to be published with Boydell and Brewer in 2019.

About John Pollock

John Pollock went to the University of Oxford, and he has conducted research at the Manchester University and for the UK Government. Recent work includes reports on the Arab uprisings, the Libyan War, and on Russian disinformation for MIT Technology Review.