By Sophie Chiari and Mickaël Popelard

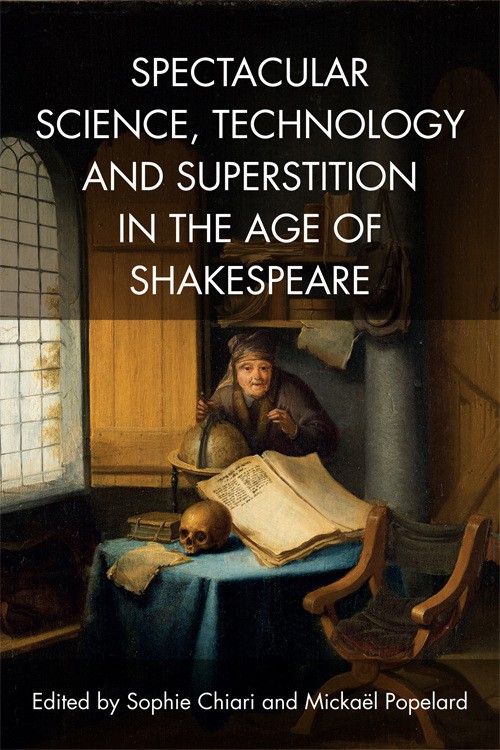

In this two part quiz, the editors of new book Spectacular Science, Technology and Superstition in the Age of Shakespeare pose some interesting questions in relation to Shakespeare and science and go on to quote from the book in answer to them. The second part of the quiz will be published next week.

- Can you explain the precise difference between natural astrology and judicial astrology?

Page 30, François Laroque: “Natural astrology was concerned with general planetary influences, such as those on nature and agriculture or those on the human body in the medical field. Judicial astrology consisted in relatively precise predictions, derived from the respective position and influence of the planets, that were intended as advice to individuals: a nativity, or horoscope, was based on the map of the heavens at the time of a person’s birth; elections denoted the process of choosing the most propitious moment, i.e. when the planets were most favourable, such as for a king’s or queen’s coronation, for example; finally there were horary questions when the astrologer tried to resolve personal problems according to the state of the heavens when the question was being posed.”

- Why is Shakespeare’s Juliet an astrological, yet also poetic, link between the sub- and the translunary world ?

Page 49, François Laroque: “As ‘jewel’, Juliet becomes ‘starified’, or rather her eyes become stars. She transcends the division between human life and cosmic life, between the sub- and the trans-lunary world: ‘Two of the fairest stars in all the heaven, / Having some business, do entreat her eyes / To twinkle in their spheres till they return. / What if her eyes were there, they in her head? – / The brightness of her cheek would shame those stars / As daylight doth a lamp; her eye in heaven / Would through the airy region stream so bright / That birds would sing and think it were not night’. (2.1.57–64). The eyes/stars chiasmus is both a Petrarchan cliché and an astrological allusion grounded in the idea that the heavenly bodies are made of the same elements as human bodies.

- Did you know that the myth of Phaeton was one of the first climatic myths in European history?

Page 49, François Laroque: “In the Renaissance, the Phaeton myth was associated with the canicular myths, as Rabelais’s Pantagruel shows (Rabelais 1994: 223, chap. 2). Ovid’s fable was the first to express fears about growing heat and climate change, fears that were often associated with apocalyptic visions of a world destroyed by fire. Indeed, one of the marginal notes of the Phaeton episodes refers to the following quotation as ‘the burning of the world’ (Golding 2002: 69).”

- How could early modern witches influence the weather according to Scot’s The Discoverie of Witchcraft?

Page 49, Pierre Kapitaniak: “In Act 1, scene 3 [of Macbeth], the witches evoke their power to create winds (‘I give thee a wind’; 1.3.11), which is also one of the first faculties that Scot mentions about witches:

Such faithlesse people (I saie) are also persuaded, that neither haile nor snowe, thunder nor lightening, raine nor tempestuous winds come from the heauens at the commandment of God: but are raised by the cunning and power of witches and coniurers; insomuch as a clap of thunder, or a gale of wind is no sooner heard, but either they run to ring bels, or crie out to burne witches. (Scot 1584: 2)”

- What is “cruentation” and how was it used in forensics to solve early modern criminal cases?

Page 51-52, Pierre Kapitaniak: “Surprisingly, editors of the play delve into James’s Dæmonologie to document the last line of Macbeth’s speech with his opinion on cruentation (the fact that a corpse will bleed in the presence of the murderer), forgetting that, long before James, Scot had already commented on a similar phenomenon in The Discoverie and, despite his general scepticism, allowed for its reality (Scot 1584: 303–4; Muir 1977: 97; Clark and Mason 2015: 227).”

- Did you know that gynecology (re-)emerged as a distinct area of medical expertise in the 16th century?

Page 68, Sélima Lejri: “In particular, the explorations in the field of gynaecology roused much attention and caused it to develop into a specialised topic of medical expertise. This was mainly attributable to the Galenic theories of humours and vapours but also to the Hippocratic treatise Diseases of Women, which was translated from Greek into Latin as early as 1525 (Peterson 2010: 3). Consequently, the human body and its long-hidden mysteries were uncovered from those ancient physicians under the fascinated eyes of the Elizabethan anatomists (Sawday 1995: 266).”

- Did you know that hysteria, in early modern England, was a fundamentally gendered disease?

Page 74, Sélima Lejri: “Likewise, sixteenth- and seventeenth-century physicians understood the pathology of love on the basis of gender, whereby hysteria was the terminology attributed to the feminine equivalent of masculine lovesickness, called ‘amorous melancholie’ by Andreas du Laurens in his Discourse of the Preservation of Sight (1597) (Wells 2007: 3; Thomas Neely 2004: 103). Moreover, they recognised hysteria as ‘a sort of Madness’, as in Riverius’s description in The Practice of Physick (1655) (Eccles 1982: 82), or again as furor, as in the quasi-scientific analysis Lucretius makes of it in his influen- tial De rerum natura (Lucretius 1998: IV, 1,030–191). Nevertheless, they gave it diverse names such as hysteria or hysterica passio, womb-fury or furor uteri, and even the Suffocation of the Mother, or Suffocatio and Strangulatus uteri (Gilman 1993: 12–13).”

- Do you know who Mary Glover was?

Page 79-80, Sélima Lejri: “A fellow of the College of Physicians, Jorden centres his medical study on the highly topical case that captivated the attention not only of the citizens of London, but also of King James VI on the eve of his accession to the throne of England (Paul 1950: 107). The case is that of Mary Glover, a teenage girl allegedly bewitched by an old lady, Elizabeth Jackson, who caused her a formidable array of somatic torments daily, from spectacular writhing to comatose-like syncope […]. The debate over this case came to a head with the imprisonment of the presumed witch and resulted in a ‘pamphlet war’ (Paul 1950: 106). The king received two conflicting testimonies as to the validity of Mary Glover’s bewitchment. Jorden’s recently printed book, then consulted by the king, disrupted the supernatural interpretations of the girl’s symptoms in favour of a scientific explanation of hysterica passio combined with melancholy, all due to an imbalance of humours […].”

- Which, would you say, is Shakespeare’s most musical play – i.e. the play with the greatest number of lines sung?

Page 85, Pierre Iselin: “First of all, [Twelfth Night] is the play with the greatest number of lines sung in Shakespeare’s whole canon. It is also the only play that has a musical opening – not the traditional trumpet call, but more likely the music of a mixed consort. It is also a play whose musical epilogue confronts audiences and directors with the question of the limits of representation. So, more generally, one can wonder if the abundant stage music is in excess in Shakespeare’s comedy. Is not the play as a whole stricken with ‘melomania’? And in that case, for whom does the music sound ?”

- Have you heard of Timothy Bright’s musical treatment for melancholy?

Page 86, Pierre Iselin: “The musical treatment of melancholy, in particular, is discussed by Timothy Bright, a medical doctor and divine whose Treatise of Melancholy (1586) gives precise recommendations concerning both food and music:

As pleasant pictures, and lively colours delight the melancholicke eye, and in their measure satisfie the heart, so not onely cheerfull musick in generalitie, but such of that kinde as most rejoyceth, is to be sounded in the melancholicke eare. (Bright 1969: 301)”

- What rather surprising effect was music believed to exert on man (at least according to Puritans like Philip Stubbes)?

Page 89, Pierre Iselin: “Penetrating the soul through the ears – like food through the stomach – music arouses sexual desire and deprives man of his masculinity, making him ‘womanish’, as it rapes him (‘ravisheth the hart’)”, [according to Philip Stubbes].

- Do you know what “Entelechy” is?

Page 104, Margaret Jones-Davies: “Entelechy is the last stage of Alchemy, when the four elements are conjoined in the fifth essence or quintessence, the pure essence of the philosopher’s stone, which can preserve from destruction; the elixir that can cure disease, rejuvenate, and even resurrect the dead (Abraham 1998: 75). In Rabelais, the rejuvenation is not due to the miraculous powers of the elixir but to a venereal disease of the type of pelada, which sloughs off the old skin.”

- Could you define “uroboros”?

Page 111, Margaret Jones-Davis: “The perfection of the alchemical figure of the uroboros, a circle made by a serpent eating its own tail, brings out once more the paradox implied in the achievement of perfection. For here the serpent both destroys and nourishes itself.”

- Did you know that Lucretius actually never uses the word atomus in his De Rerum Natura?

Page 123-24, Jonathan Pollock: “However, Lucretius, in his attempt to acclimatise Epicurean doctrine to the Roman world, never uses the word atomus to translate atomos, nor even its strict Latin equivalent, individuum (‘indivisible’). In order to explain what atoms are, he is accustomed to calling them the matter or genital bodies of things, and more often than not the seeds of things: ‘quae nos materiem et genitalia corpora rebus / reddunda in ratione uocare et semina rerum’ (DRN, 1.58–60). When referring to ‘the school of Leucippus and Democritus and Epicurus’ in his essay ‘Of Atheism’, Francis Bacon will follow Lucretius’s example and translate atomoi by ‘seeds’: he can scarcely believe ‘that an army of infinite small portions or seeds unplaced should have produced this order and beauty without a divine marshal’ (Bacon 2000b: 51).”

Tune in next week for the second part of this quiz! Spectacular Science, Technology and Superstition in the Age of Shakespeare edited by Sophie Chiari and Mickaël Popelard publishes September 2017.

Sophie Chiari is Professor of Early Modern English Literature at Clermont Auvergne University, France. She has written several books and articles on Shakespeare and his contemporaries. Her most recent publication is As You Like It: Shakespeare’s Comedy of Liberty (2016).

Mickaël Popelard is Senior Lecturer in English studies at the University of Caen Normandie, France. He has written several articles on Shakespeare and Bacon, as well as a book on the figure of the scientist in Shakespeare’s The Tempest and Marlowe’s Doctor Faustus (Rêves de puissance et ruine de l’âme: la figure du savant chez Shakespeare et Marlowe, 2010).