By Catriona M.M. Macdonald

Historians frequently address reputations in their work, indeed they are central to some of the most important debates in historiography. They are typically less inclined, however, to address common assumptions regarding the work and legacy of their forebears (especially the black sheep of the academic family), except perhaps fleetingly in footnotes. While denying Whiggish approaches to history itself, they tend to rest content in the knowledge that bona fide historical scholarship invariably improves as each new generation succeeds the former and – while applauding public intellectuals – they are comforted by the fact that professional conventions guard the academic field at least from charlatans and amateurs.

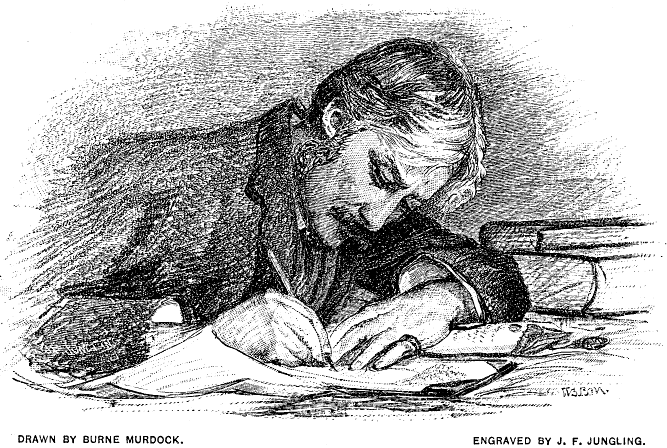

The work and posthumous reputation of Andrew Lang (1844-1912), however, unsettles accepted wisdom on the evolution of Scottish historical scholarship in the nineteenth century and its influence on twentieth-century studies. While seldom cited in histories nowadays, Lang was a prolific and popular historian in his own life-time, publishing a multi-volume history of Scotland, biographies of Knox, Mary Stuart, MacKenzie of Rosehaugh and John Gibson Lockhart (the biographer of Walter Scott), not to mention editing the works of Burns, Scott and Stevenson. Writing as an independent author out-with the academy, however, and appearing regularly as a columnist in the London cultural journals of the day – not to mention his deserved reputation as a classicist, anthropologist and purveyor of fairy stories – was problematic. Caricatured as a dabbler in history, attacked for a journalistic style, dismissed for his focus on romantic historical episodes and treated with contempt at times as a ‘London Scot’, Lang seemed out of step with Scottish historical studies at a time when they were seeking a place in university curricula and when history (proper) turned its back on romanticism in its pursuit of scientific status.

Yet there’s more to Lang than that. As my article in the Scottish Historical Review shows, by integrating Lang into Scottish historiography, much is to be gained. Among other things, Lang’s life and work encourages us to look again at the persistence of romance in serious history; asserts the significance of a reading public in determining historical sensibilities; throws into disarray the simple binaries of scientific/ romantic; Whig/ Jacobite; unionist/ nationalist that have patterned our understanding of history in the fin de siècle years; and questions common assumptions regarding the Anglicisation (or inferiorisation) of Scottish historical scholarship. The absence of an influential political nationalist movement in Scotland in these years has for too long been used as a measure of Scotland’s intellectual impotence. Lang’s reputation suggests that things were far more complex. According to Lang in 1911, he was ‘A Scot whose critics in England banter him on his patriotism, while his critics in Scotland revile him as rather more unpatriotic than the infamous Sir John Menteith, who whummled the bannock’.

Read Catriona’s article ‘Andrew Lang and Scottish Historiography: Taking on Tradition‘ in the Scottish Historical Review, 94.2.

Catriona M.M. Macdonald is Reader in Late Modern Scottish History at the University of Glasgow. A former editor of this journal, she is also the author of Whaur Extremes Meet: Scotland’s twentieth century (Edinburgh, 2009)—winner of the Saltire Society History Book of the Year, 2010.

Picture credit: Engraving of Andrew Lang at Work. . Wikimedia Commons.