By Giovanni Gellera

Until recently, the question ‘What was philosophy like in Scotland before the Enlightenment?’ met a standard answer reminiscent of the famous Augustinian warning to those who dared to ask what was there before the beginning of time: ‘Hell, for those who ask such a question!’ Jokes aside, when I started to work on Scottish philosophy people did not really know what seventeenth-century Scottish philosophy was like ‒ they were not even sure if there had been a thing called ‘seventeenth-century Scottish philosophy’. Studies on seventeenth-century Scottish philosophy are now in full (re-)naissance. The intellectual map of an important and long-forgotten chapter of the history of Scottish philosophy is gradually revealing its mountains ranges, plains and coastlines before our eyes.

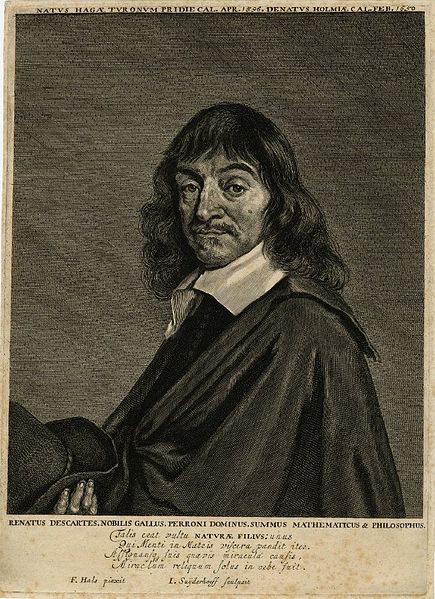

My article investigates the fortune of the great René Descartes (1596-1650) in the Scottish universities in the period 1650-1680. Far from swimming in a philosophical backwater, the masters of Arts in the Scottish universities were very receptive of the momentous developments taking place on the Continent. The novel philosophy of Descartes arrived in Scotland, where the university philosophers swiftly made it their own. This is what I like to call the ‘Cartesian consensus’: a general positive attitude towards Descartes, and what Descartes was thought to represent: freedom of philosophy, empirically-minded research, optimism about human reason, and confidence in science.

Descartes would have probably not recognised himself in most of the teachings of the Scottish Cartesians. This suggests that seventeenth-century Scottish philosophers were not passive receptors of philosophical gains made elsewhere; rather, they were the epigones of a lively scholastic tradition and produced their own original version of Cartesianism. These intellectual achievements deserve due acknowledgement in the history of Scottish philosophy.

Descartes was a controversial figure in the seventeenth century. ‘Love him or loathe him’, really! The Scottish philosophers by and large loved him. I sense this tells us something profound about seventeenth-century Scottish universities: the roots of the Enlightenment to come were already there, in the openness to a new philosophy, and in the freedom of teaching it.

Read Giovanni’s article free online: ‘The Reception of Descartes in the Seventeenth-Century Scottish Universities: Metaphysics and Natural Philosophy (1650–1680)‘.

Giovanni Gellera is Research Affiliate at the School of Humanities, University of Glasgow.  He was awarded his Ph.D. from the University of Glasgow in 2012 for a thesis on the teaching of natural philosophy in the seventeenth-century Scottish universities. He was member of the Leverhulme project Scottish philosophers in 17c Scotland and France (2010-14) which is producing the first history of seventeenth-century Scottish philosophy. He has published in the Journal of Scottish Philosophy and in the British Journal for the History of Philosophy. For EUP, with Alexander Broadie, he is editing and translating the recently discovered Idea Philosophiæ Moralis (1679) by James Dundas, First Lord Arniston.

He was awarded his Ph.D. from the University of Glasgow in 2012 for a thesis on the teaching of natural philosophy in the seventeenth-century Scottish universities. He was member of the Leverhulme project Scottish philosophers in 17c Scotland and France (2010-14) which is producing the first history of seventeenth-century Scottish philosophy. He has published in the Journal of Scottish Philosophy and in the British Journal for the History of Philosophy. For EUP, with Alexander Broadie, he is editing and translating the recently discovered Idea Philosophiæ Moralis (1679) by James Dundas, First Lord Arniston.