by William E. B. Sherman

O you mangled souls: fear the sigh of the dervish.

It’s a sigh exhaled by passioned love for God

that burns the mountains to ash like straw.

…

If you see with the eye of your heart,

everywhere will you witness the Lord.

If you hear with the ear of your heart,

all sounds are but praise of God.

All creatures around you

are but creations of God, the One.

The lovers believe,

the ignorant deny,

and Arzānī speaks Pashto,

again, again, again, from the depths of his heart.

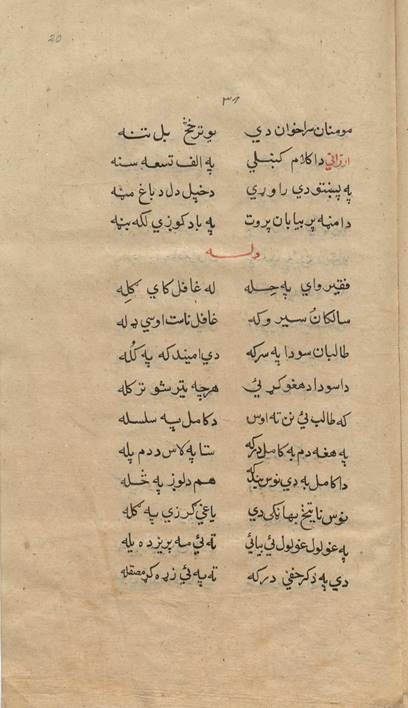

[Verse 20b-21a]

How might a poet with dreams of messiahs and mystics help us rethink histories of ethnicity, religion, and literary transformation in the regions that would become Afghanistan? Just around the year 1600 CE, a poet known as Mulla Arzānī wrote the verses above in Pashto. Though Pashto (also called “Afghan” or “Pukhtu”) had been identified as the spoken language of Pashtuns and other Afghans for centuries, Mulla Arzānī’s poems are among the very earliest examples of written Pashto literature that we have.

Though Pashto literature emerged in multiple spaces for divergent reasons to become eventually an official language of Afghanistan as well as the primary language of millions of Pashtuns, one particular emergence of Pashto as a written language of literature can be traced to a group of Sufi Muslims who understood the world to be on the cusp of apocalyptic transformation and messianic revelation. For them, the sacred language of God was not confined to the Qur’an’s Arabic; something divine infused Pashto as well, at least when written and composed by a spiritual master such as Arzānī and his teachers.

Arzānī was a disciple of the pir-i roshan (“the illuminated master”) Bayazid Ansari, who led an eclectic band of nomads, widows, orphans, and poets in an armed rebellion against the armies of the Mughal emperor Akbar. The political and military successes of Bayazid’s followers—collectively remembered as the Roshaniyya—were short lived, but their imaginations sparked some profound changes in the poetic worlds of Pashto language. As hinted in the verses above, Bayazid Ansari, Mulla Arzānī, and the Roshaniyya understood their Pashto as the key to hearing the voice of God in all of creation —and even speaking God’s language anew.

As we turn to mystical and messianic musings of Arzānī’s ghazals, there is more at stake here than the literary interpretation of a particular poet. Indeed, there’s more at stake than understanding the seething diversity of Islam as practiced in the interconnected cultural regions of Iran, Afghanistan, and South Asia.

Beyond this, we can also allow Arzānī’s poetry to help us rethink contemporary habits of approaching history. English-language scholarship on the history of Afghanistan and Afghans continues to bear the considerable imprint of imperial historiography that explained so much of Afghan culture, religion, and politics by appealing to notions of tribe and ethnicity.

Previous scholarship has framed the poetry of the Roshaniyya and their mystical texts as the literary expressions of Afghan rebellion against Mughal domination, of a burgeoning Afghan self-consciousness, and as vernacular expressions of ethnic mobilization. In short, Pashto is for Pashtuns striving to create a Pashtunistan.

However, the poetry of Arzānī does not fit this mold. There is little indication that Arzānī tethers the Pashto-ness of his poetry to communal, ethnic identity. Quite to the contrary, for Arzānī it seems that Pashto is a means to explore transregional messianic ideas further. Or, in other words: the “Pashto-ness” of his poetry is significant because it mimics Persian and Arabic discourses and then transcends them in a new divine and divinizing language. For Arzānī, Pashto is not a means to speak to the Pashtun public but the path to claiming his place among the spiritual and saintly elite.

In one of his longer ghazals, Arzānī explores the sins of Adam and the arrogance of Iblis. The poem begins with the forbidden fruit and concludes with a different garden:

[Arzānī wrote this poem] in Pashto

in the garden that is his heart.

An apple tree planted in the desert

will wither and fall in the wind.

[Verse 20a-20b]

(Source: Arzānī. Dīvān-i Arzānī. N.D. London: British Library, MS Or. 4496, fol. 20b.)

In which garden might we best understand Arzānī’s Pashto poems? Arzānī’s was an approach to language that might strike some as strange for the way it eludes many assumptions about the history of Afghan cultures and religion. Rather than a matter of protonationalism and ethnic identity, we might understand Arzānī best according to logics and imaginations of belonging, language, and messianism that wound throughout the Persianate world. Rather than in the interpretative worlds conjured and imposed by outside observers and scholars, Arzānī’s Pashto blooms in a garden specific to his time and his place.

Read William E. B. Sherman’s article here: In the Garden of Language: Religion, Vernacularization, and the Pashto Poetry of Arzānī in the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries.

Find out how to subscribe to AFG, recommend to your library, sign up for Table of Contents alerts, and submit a paper.

About the journal

Afghanistan is the journal of The American Institute of Afghanistan Studies, dedicated to the cross-cultural study of Afghanistan and its surrounding regions, delving into its rich history from a wide variety of humanities-focused angles. The journal covers all subjects in the humanities including: history, art, archaeology, architecture, geography, numismatics, literature, religion, social sciences and contemporary issues from the pre-Islamic and Islamic periods.

Delve into the latest journal issue here.

About the author

William E. B. Sherman (B.A., Stanford University; M.A., University of California, Los Angeles; Ph.D., Stanford University) joined the UNC Charlotte faculty in fall of 2017. His research approaches the history and literature of Muslim societies with a particular focus upon premodern South and Central Asia. His research engages the imagination of language and revelation in premodern Islamic culture.

Want to keep up with all of the latest content from Edinburgh University Press? Sign up for our newsletter.