It’s been fifteen years since the last fat volume of essays on contemporary Scottish writing. Only a blink of historical time, but it’s been quite an eventful period. When the chapters of Berthold Schoene’s brilliant Edinburgh Companion to Contemporary Scottish Literature were being written, both the country and its debates looked rather different.

Suddenly I see…

When that book appeared in 2007, KT Tunstall was on the radio, New Labour was dominant, and the biggest story in UK politics was the Blair-Brown succession. (Only anoraks had heard of Nigel Farage.) There was no SNP government until May of that year, and the 2006 smoking ban prompted more heated arguments than constitutional change. Scotland had two national newspapers which have since vanished or been absorbed into sister titles, and a new ‘microblogging’ platform was beginning to emerge as a credible challenger to MySpace. Bella Caledonia launched in October 2007, a lippy upstart seeking to disrupt Scottish journalism and arts coverage. Today, this blog is one of the taller landmarks still standing in the wasteland of Scottish media. There has been muscular nation-building since 2007 but also an alarming loss of capacity (especially in book and theatre reviewing).

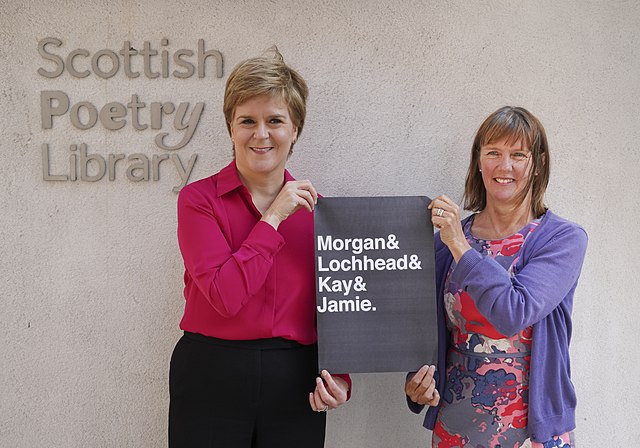

Literary developments would include an explosion of nature writing and crime fiction, especially by women, with energetic developments in Scots poetry and the contemporary Gothic. In 2007 there were no books by Jenni Fagan, David Keenan or Kirstin Innes, and film-poetry wasn’t really a thing. Even previously established names look quite different today. Kathleen Jamie has become as widely known for her essays as for her poetry, and succeeds Edwin Morgan, Liz Lochhead and Jackie Kay as National Makar. Ali Smith has become the leading literary novelist of contemporary Britain. David Greig and Louise Welsh are not just successful artists, but important mentors and institutional supporters of new writing.

A whole swathe of the contemporary ScotLit landscape – writers as well as critics – can scarcely recall a time before devolution, and this alters the questions they bring to bear on familiar debates about language, place, identity. So it was time for a fresh look, attending to new voices and forms, while almost accidentally beginning to redress long-standing imbalances in who publishes Scottish criticism. (Though not a deliberate plan, eleven of our chapter authors turned out to be women, while five are men.) The book also re-examines the critical tools and narratives we use to make sense of Scottish writing in the contemporary moment. As the blurb says, it attempts a ‘provisional re-mapping’ of the post-devolution scene, exploring how literature, theatre and visual art have both shaped and reflected the ‘new Scotland’ promised by the new Scottish Parliament.

Devolutionary paradigms

The critical paradigms of the 1990s emerged within a clear narrative of democratic emergence, mapping a confident ‘new politics’ onto the nation’s literary culture. In this story, Scottish Literature would recover its canon, infrastructures and public standing within a broader renovation – and imaginative re-founding – of national life. In 2007, Schoene used the term ‘post-devolution Scottish Writing’ to capture Scotland’s ‘transition from subnational status to devolved home-rule independence’. This slightly blurred chain of political descriptors – ‘devolved home-rule independence’ – captures precisely the difference between Schoene’s ‘post-devolution’ and our own. ‘POLITICS WILL NOT LET ME ALONE’, says the antihero of Alasdair Gray’s 1982 Janine. While the politics of nationhood have always been a constitutive factor in the endeavour we call Scottish Literature (at once creative, critical, commercial), never before has constitutional debate tugged so insistently at the field’s collective sleeve.

The hallmark of our own scholarly moment is to feel an uncanny continuity between political argument and the stakes and subtexts of Scottish criticism. Until recently, Scottish literary nationalism viewed itself in the vanguard of a broad civic movement which moved outside and ahead of party politics. Today its cause and domain have been reclaimed by a truly mass nationalist movement quite different from the 1980s republic of letters evoked by Cencrastus magazine and Edwin Morgan’s Sonnets from Scotland.

Edges of the new?

Wherever this movement leads, it seems unlikely that writers and intellectuals will shape its future direction (as opposed to cheering or booing from the sidelines, in varying degrees of enthusiasm, anguish or half-belief). The impossibility of skirting these questions is a key lesson of our times, and this collection aims to directly address the political field in which it is located, including reflections on post-indyref Scotland. To be ‘post-devolution’ in 2022 means not simply ‘after 1999’, but after everything the new parliament made possible: after 2011 (and the SNP’s mandate to call an independence referendum); after 2014 (and indyref’s remaking of cultural and political debate, both creative and destructive); after the SNP surge of 2015 (and the growing hegemony of Team Scotland arguments from identity, prominent in the field’s own history); and after the Brexit shock of 2016 (eclipsing the dream-horizon of ‘Scotland in Europe’, while underscoring its appeal). As critics today, our devolutionary belatedness amounts to feeling, reading and writing somewhat ‘stuck’ within a framework tending both to entropy and repetition.

So the ‘edges of the new’ pursued in this book are also new horizons of memory, looking back on devolution from points ‘beyond’ its 1990s paradigms (political, cultural, intellectual), but also caught within them. If Scottish literature’s narrative of emergence and ‘ImagiNation’ had a clear teleology of fresh growth (new parliament, new confidence, new possibility) in past decades, today we handle the blunted edges of devolution as an established and somewhat fatigued condition, while wondering how it might lead beyond itself.

About the author

Scott Hames is Senior Lecturer at the University of Stirling, where he led the MLitt programme in Scottish Literature. He edited Scottish Writing After Devolution (Edinburgh University Press 2022) along with Marie-Odile Pittin-Hedon and Camille Manfredi. Wrote The Literary Politics of Scottish Devolution: Voice, Class, Nation (Edinburgh University Press, 2019) and edited the Edinburgh Companion to James Kelman (Edinburgh University Press, 2010) and Unstated: Writers on Scottish Independence (Word Power Books, 2012).

Sign up to our mailing list!

If you’re interested in staying up to date with events, discounts and new releases from Edinburgh University Press please sign up to our mailing list here!