By Bryony Coombs

In March 2020 I was working in the Mitchell Library in Glasgow, conducting research on a fifteenth century manuscript, a Latin chronicle of Scottish history. This was fortuitous timing, as one week later the UK entered a nationwide lockdown due to the outbreak of COVID-19.

In May 2021, I made a long-awaited return to the archives, this time to the CRC at Edinburgh University Library. The manuscript I was consulting in this case again dealt with Scottish history, a historiographical work by an early-eighteenth century scholar, Thomas Innes, and his research notes on various medieval Scottish histories.

These two experiences, and the gulf of time separating them, have given me cause to consider the nature of researching, and teaching, using medieval manuscripts, and what happens when we cannot access them. In teaching a course this past year that focused on manuscript material, I have grappled with this shift from a hands-on approach, to remote engagement through digital facsimiles. This has raised all kinds of questions relating to what is lost, and what is gained, by this shift in pedagogy.

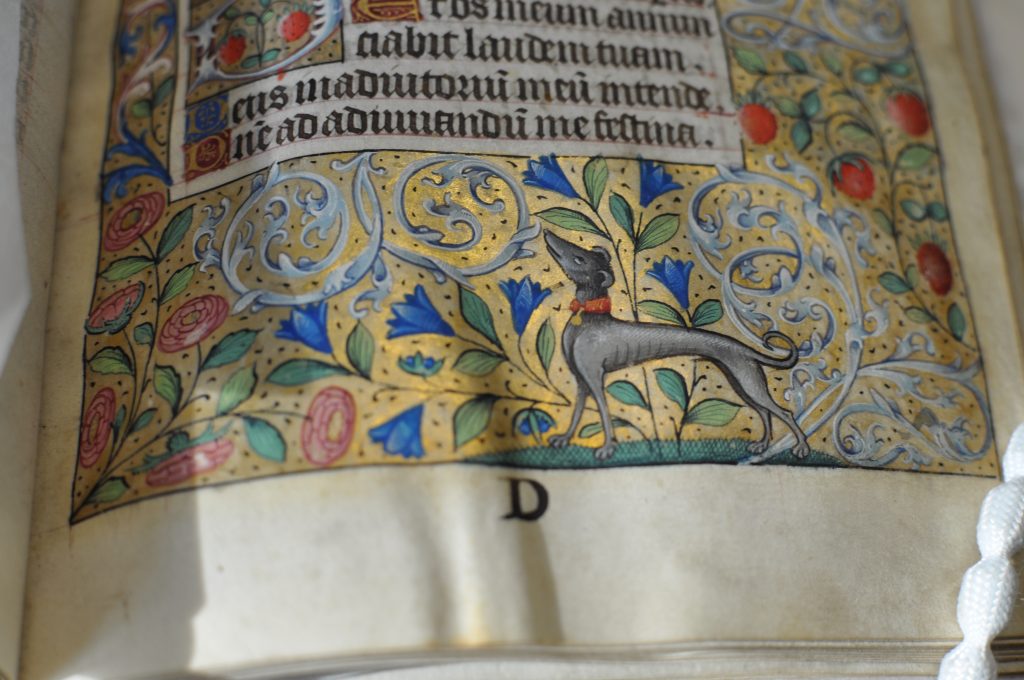

Huge advances in the digitisation of manuscript repositories over recent years mean that medieval manuscripts are more accessible than ever before. But electronic access has its downsides, the inherent sensory loss of the experience of examining these objects at first hand is unavoidable. The manuscript is a tactile object, constructed of fine sheets of vellum – literally skin. It was made to be held, the folios to be turned, the details to be scrutinised. It was, and is, a performative object that rewards close observation and slow, careful examination. The most innovative digitisation methods to date cannot replicate the play of light on an illuminated initial, or give a sense of the texture of parchment between fingers, the smell of vellum, and the sound of pages turning. They cannot replicate the embodied experience of researching a manuscript at first hand. There has been a great deal written about a loss of sensory touch during the pandemic, and for researchers of manuscripts this has extended to a loss of contact with the object of their study.

In a paper I published with the Scottish Historical Review on a manuscript of Virgil’s works made for King James III of Scotland, I examined the complexity of producing such a manuscript. In this case the figures involved included the author, the Italian scribe or translator, artists from the Netherlands and France, the recipient of the manuscript in Scotland, and the patron who was responsible for initiating the whole complex project. It was a truly international collaborative enterprise, and laid bare the complex nature of producing a high-quality illuminated manuscript in the mid-fifteenth century. Manuscripts are multifaceted objects and teasing out the multiplicity of roles that were involved in their production is rarely straightforward.

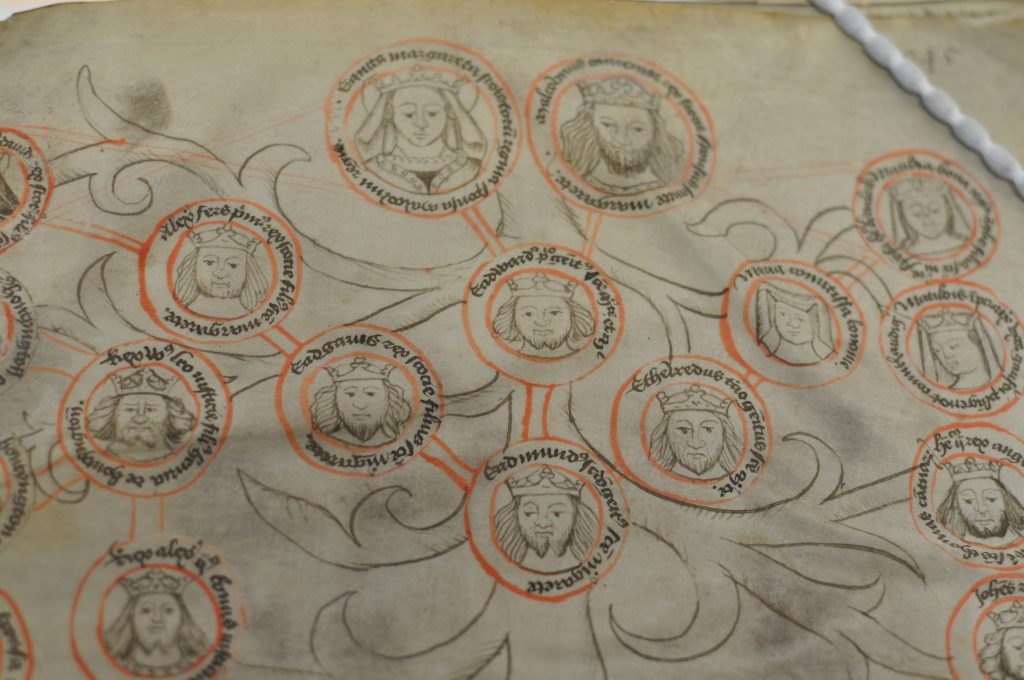

In my current research, I am looking at genealogical manuscripts of the ancient kings of Scotland. The complexities of the various figures involved, authors, scribes, artists, patrons, and readers are all investigated, but also the materiality of the manuscript. It strikes me as significant that on these sheets of vellum the painted genealogical diagrams appear to spread across the folios like living tree branches, or like veins branching beneath skin. The analogy of the vein sits particularly well in this context given that the illumination of such diagrams sought to visualise lines of descent – the bloodlines of families. These bloodlines, real or imagined, were expressed in visual diagrammatic form in order to communicate various propagandic messages, in the case of the royal house of Scotland, the creation of an ancient and autonomous line of descent upon which political authority was based.

In researching these manuscripts and the lines of blood that connect historic ruling families in these diagrams, it is noteworthy that they mirror the lines made by veins in vellum, and I am reminded of the medieval poet Alain Chartier’s declaration regarding the ancient Alliance between Scotland and France:

‘Neque enim liga hec jam in carta pellis ovine designata, sed hominum carni et cuti, non atramento, ymno sanguine mixtim fuso scripta est.’

‘The Alliance is not written on parchment in ink, but engraved on the living flesh of man’s skin in blood.’

In his oration Chartier likened a written document to a concept embodied by the people of Scotland and France. The metaphor of body and vellum, blood and ink is laid bare.

So as I settle back into hands-on research with manuscripts, this period of separation from the physical object has brought a number of thoughts to the fore; surrounding embodied viewing, the limitations of the digital, and the genealogical manuscript as a living document. Digital developments make such artefacts more accessible than ever before, but often fail to capture more than the basic visual features. The connection between the genealogical diagrams that I am studying and Chartier’s concept of the embodied document takes on a new resonance. The literary idea of an alliance etched on skin, and the concept of the manuscript as a living object, provide a new point of departure to this post-lockdown hands-on phase of research.

Dr Bryony Coombs is a Teaching Fellow at The University of Edinburgh teaching Late-Medieval Art in Northern Europe. She undertook her PhD, at Edinburgh University, focussing on Franco-Scottish cultural connections during the late-medieval and early-modern periods.

Les Abus du Monde: A French Manuscript Produced for James IV, c. 1509, The Morgan Library & Museum, MS M. 42. The Scottish Historical Review, 100:1 (2021), 109-128.

Material Diplomacy: French Manuscripts and the Stuart Kings of Scotland, Edinburgh University Library, MS 195. The Scottish Historical Review, 98: 2 (2019), 183-213.

The Scottish Historical Review is the premier journal in the field of Scottish historical studies, covering all periods of Scottish history from the early to the modern, encouraging a variety of historical approaches, with articles written by leading scholars and Scottish historians. Find out how to subscribe, or recommend to your library.