by Nicole Gonzalez

Lovely balance Andrew Neil. The open neck and rolled up sleeves tell us this is a relaxed, informal Andrew but the books remind us he is never really off the clock. It’s like Magnus Carlsen playing Ludo.

– A tweet from Bookcase Credibility, a Twitter page dedicated to playfully analysing the bookshelves of public figures — from Madeleine Albright to Tom Hanks — and whose bio statement for their page reads, “What you say is not as important as the bookcase behind you.”

First Impressions

How long would you estimate you would need to make an accurate impression of a total stranger without the aid of a conversation to assist you; using only their physical characteristics and body language alone? A few hours? Minutes? Social psychologist Nalini Ambady and her colleagues at Stanford University conducted research on forming non-verbal impressions and their work resulted in the term ‘thin slices’. Ambady discovered it takes very little time indeed for people to make on-the-mark judgments of others. In fact, these unconscious processes happen often in less than 30 seconds.

But what if the person wasn’t even there? What if you only had access to their bedroom or personal office? Could you with accuracy, intuit that person’s personality by seeing the items they own and how they arrange their spaces? Psychologist Sam Gosling, in his research and resultant publication “Snoop: What Your Stuff Says About You” asserts that you can and do.

But let’s try, shall we?

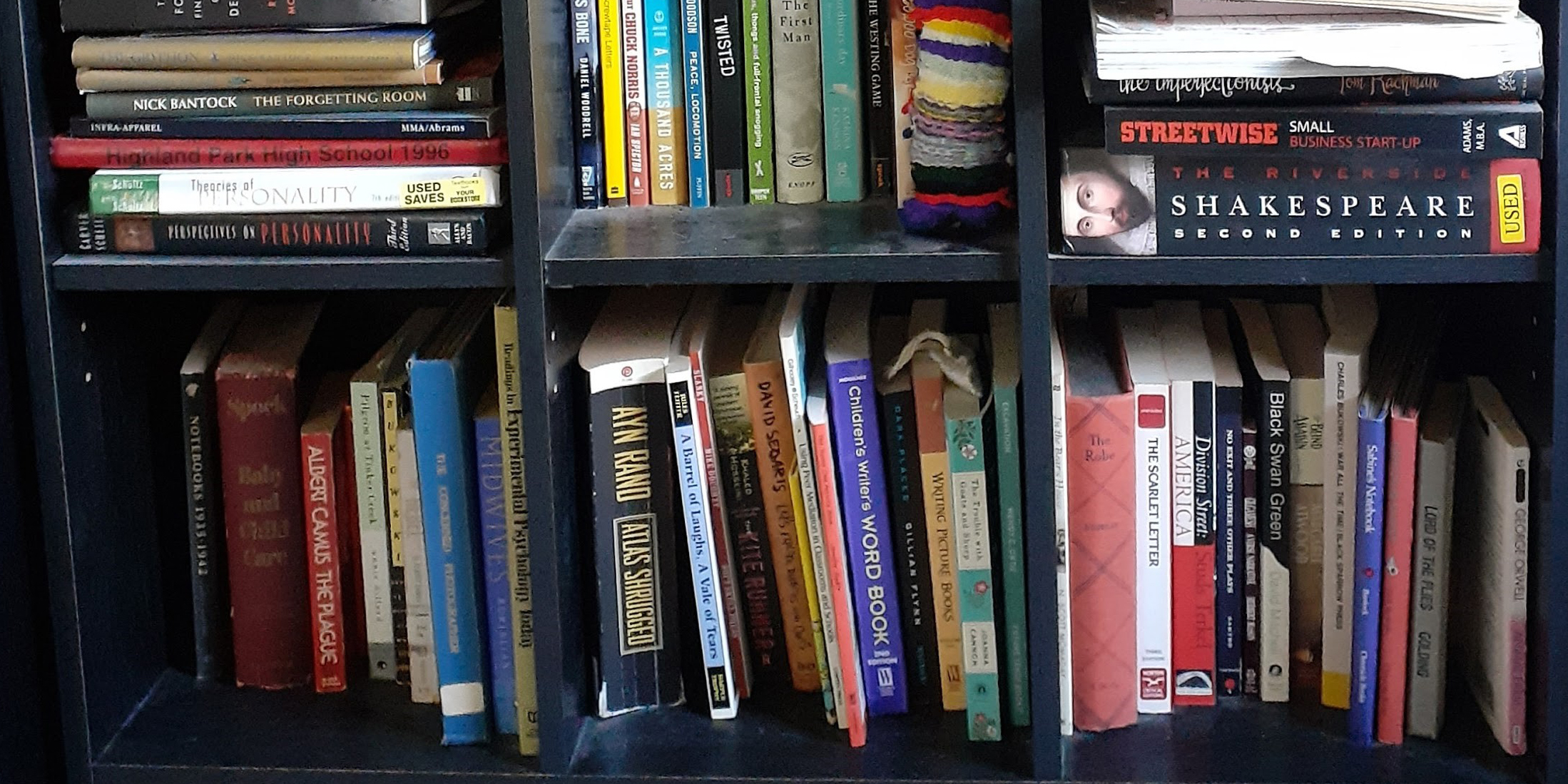

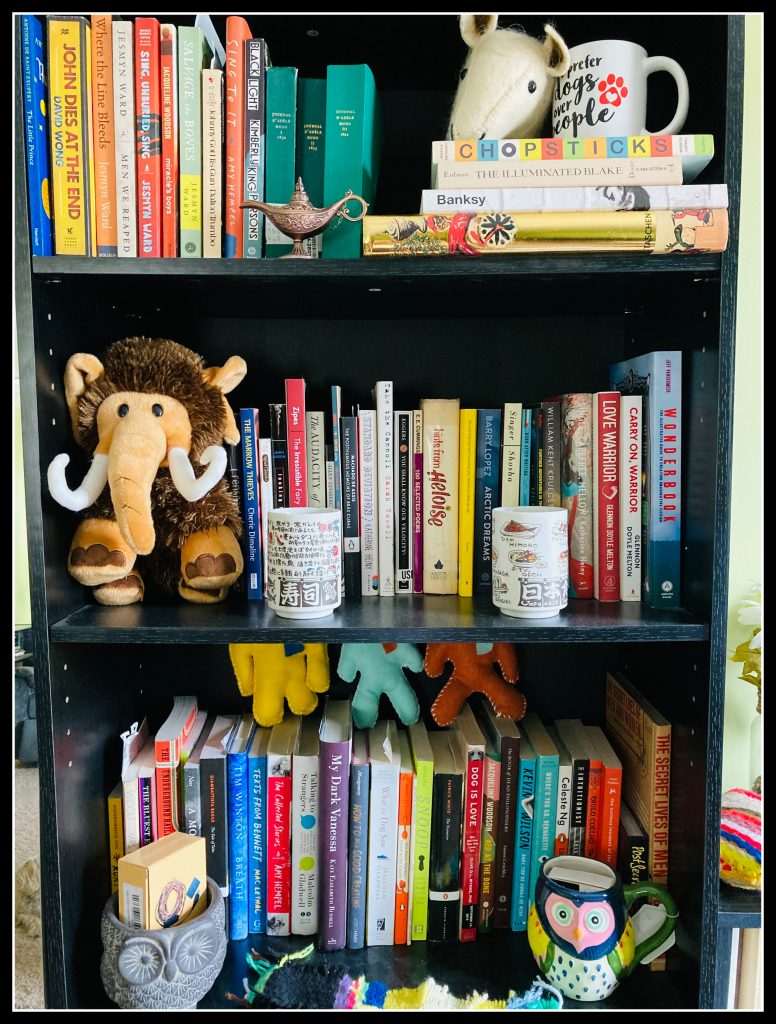

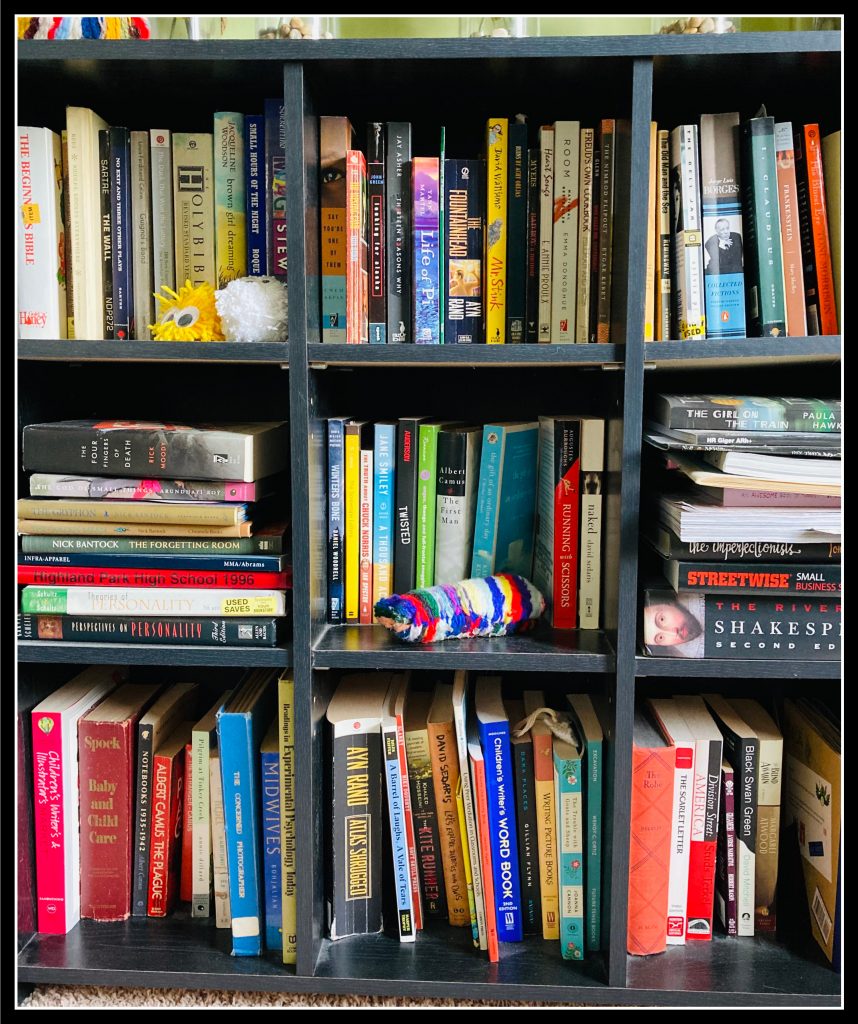

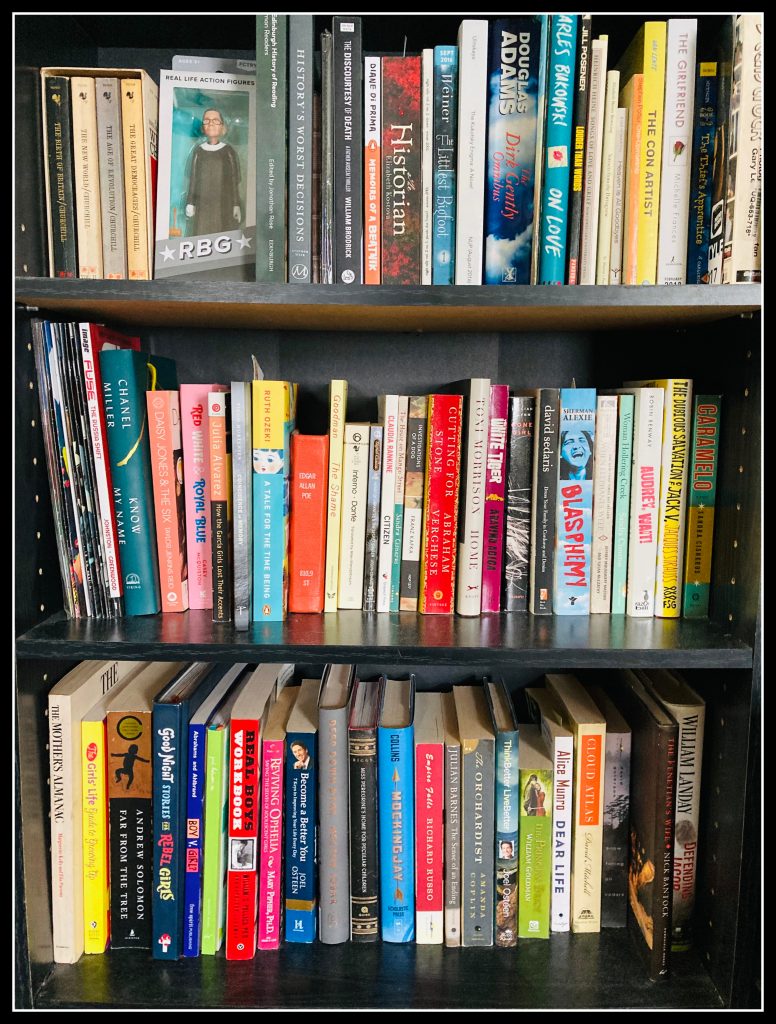

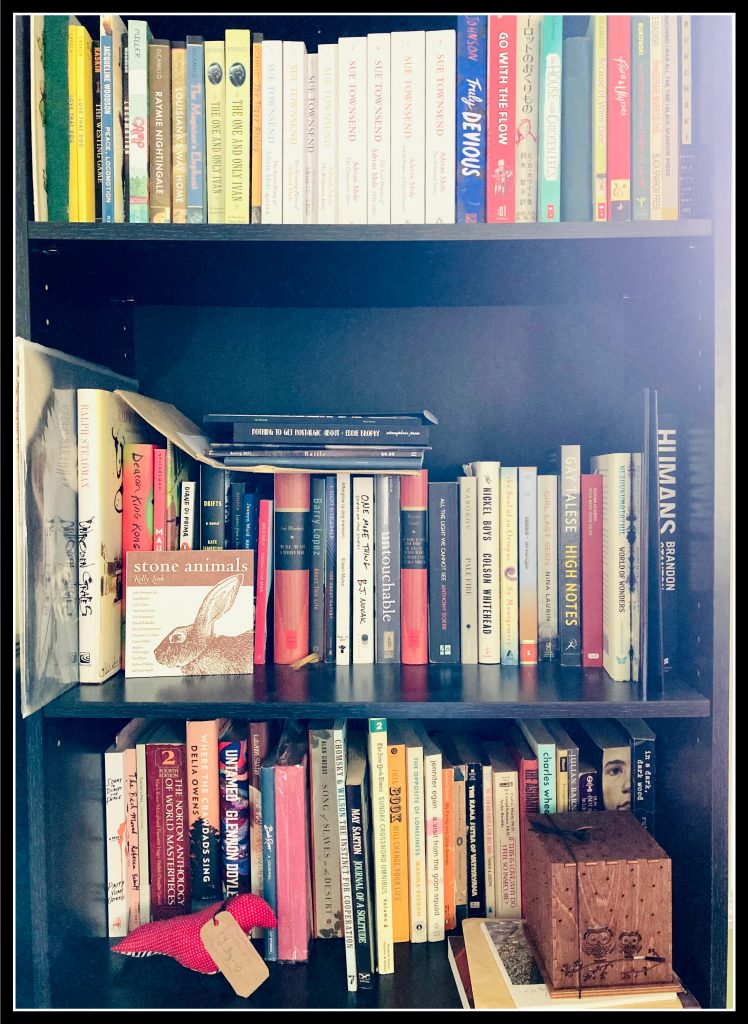

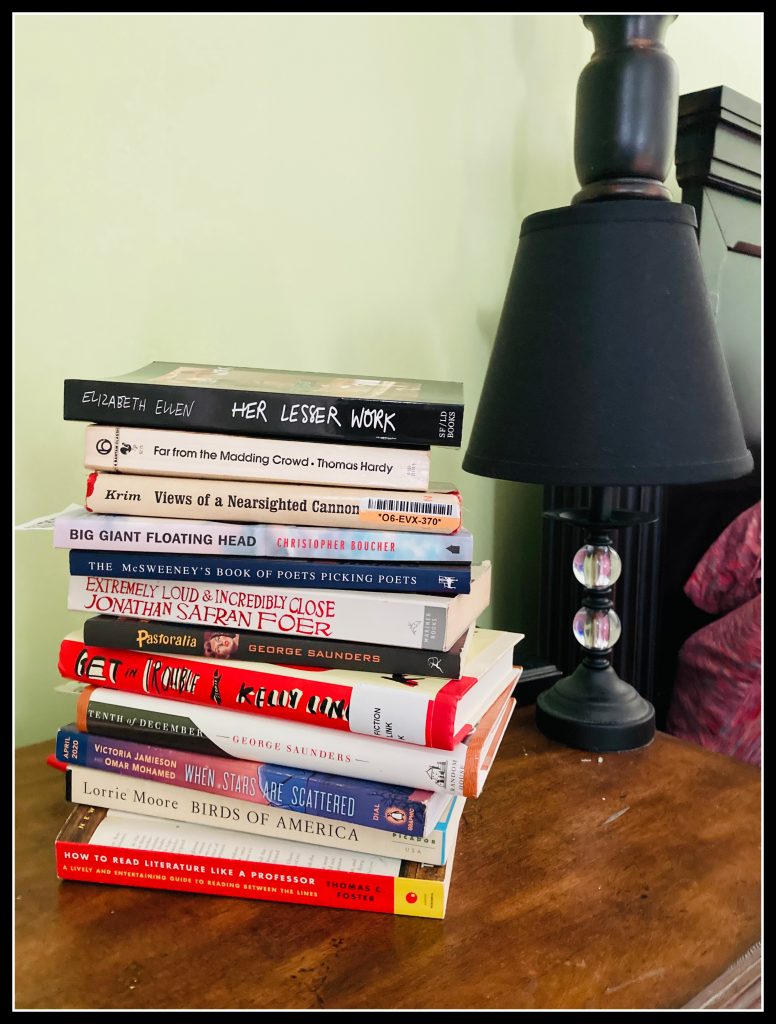

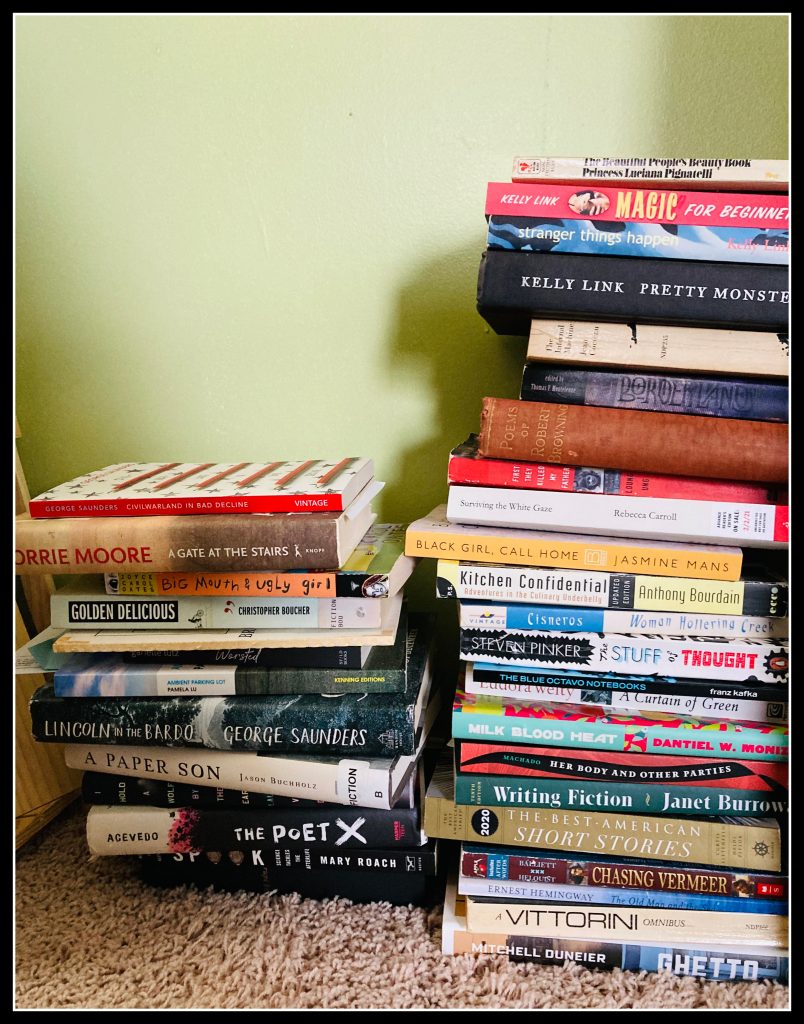

I’m going to ask you to take a look at some of my personal bookshelves in a small ‘office’ space I’ve set up in my home while my college remains offering only remote instruction. Using these photos presented (one full view and then a close up of each of the three shelves), I’m going to ask you to make an impression of me. Save for a little dusting before the photos were taken, they were unaltered. Consider as you look at them: Am I intelligent? Attractive? Am I whimsical or crotchety? Where do I fall politically? Can you suspect my sexual orientation? Do you like me?

Out Public Vs. Private (Book) Selves

Have you made your judgments? Then allow me to offer this additional detail: This ‘home office’ of bookshelves and bar table and stools is in a small corner of my bedroom. It is not a public space — my friends and neighbours are not privy to it — and, thus, these bookshelves were not curated with any intent of impressing others. They are, you might say, an authentic reflection of myself.

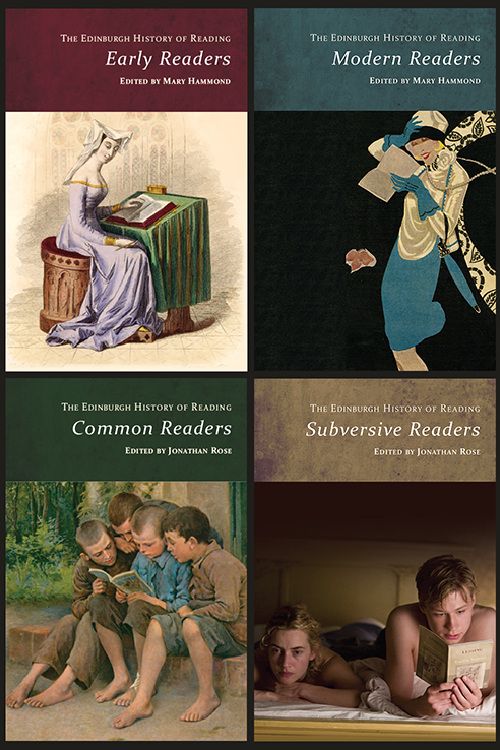

In my co-authored chapter “Putting Your Best Books Forward: A Historical and Psychological Look at the Presentation of Book Collections” in the recently published Edinburgh History of Reading Common Reader’s edition, I explore with a psychological lens the differences between people’s public bookshelves and their private ones that guests could not access. I ask, simply, why do we organize our bookshelves the way we do? Do our curations reflect something significant about us, our personalities? And, most importantly, are our private bookshelves curated differently than our public ones? Reviewing psychological literature and conducting a survey the conclusion was such: Our books are, most certainly, talking. We use them to infer information about others and we let them speak for us, as well.

As one respondent explained, “I have a few public shelves that are collectables, i.e. books that are 100 years or older. Many (75%) of these would be considered highbrow. These do not necessarily represent my tastes as a reader. Our bookshelves in our living room represent our interests and books we are proud to talk about / ‘show off’.”

The chapter, too, offers, with the contributions of my co-author, a historical investigation into the practice of curating bookshelves. This history — from Samuel Pepys’s distinguished collection (now displayed faithfully at Magdalene College) to Prime Minister William Gladstone’s published pamphlet on his detailed advice for the construction of functional bookcases to the historical phenomenon of displaying fake books (e.g. the Tianjin Binhai Library) — demonstrates that the practice of using our books to form and make an impression is nothing new.

The Post-Script I Didn’t Get to Include

It was only as my chapter was at press (my editor giving a firm “No” to post-script additions) that further evidence presented supporting the thesis. COVID-19 began its merciless spread across the countries of the world. Nooks within our homes became converted into our new offices as we adapted to the (novel for many of us) situation of working from home. As we conference remotely now still, our Zoom screens have become windows into our home lives that our co-workers can peek into.

Articles have proliferated recently demonstrating the awareness (and resultant anxiety!) that our backgrounds are feeding onlookers an impression. They offer advice on both how to convey the message and how to read the message (like this one or this.) Intrepid entrepreneurs are taking advantage marketing backgrounds that are meant to impress and social media accounts rating backgrounds have sprouted with great popularity. For example, Room Rater on Twitter.

It is no coincidence that bookshelves as the background have become a popular choice. The phenomenon so striking, in fact, a Twitter account called Bookcase Credibility has become a sensation for satirically analyzing Zoom backgrounds specifically for their books (or, in the case of Betsy DeVos, the lack of books). As Adrian Chiles posits in the title of his article for The Guardian, “The biggest status symbol of our Zoom era? Bookshelves”.

In signing off on this post, I invite you to share the impressions you made of me from (some of) my private bookshelves and share your own! As the emergent hashtags call us to do, #shareyourshelves and take a #shelfie. Let your books speak for you, as they have throughout history.

About the Series

Bringing together the latest scholarship from all over the world on topics ranging from reading practices in ancient China to the workings of the twenty-first-century reading brain, the 4 volumes of the Edinburgh History of Reading demonstrate that reading is a deeply imbricated, socio-political practice, at once personal and public, defiant and obedient.

About the Author

Nicole Gonzalez is a professor of psychology at a college in New Jersey, teaching courses that include Social Psychology and The Psychology of Death and Dying for over a decade. She is a peer reviewer for SAGE and, following her passions in creative writing now, as well, she is the editor of The Parliament Literary Journal.

Amazing!