By James Bailey

‘I am a hoarder of two things: documents and trusted friends’, wrote Spark in her 1992 autobiography, Curriculum Vitae. ‘The former outweigh the latter in terms of quantity’, she added. Spark wasn’t exaggerating; while the author was adept at weeding out fair-weather friends (‘she went through people like pieces of Kleenex’, commented the writer Ved Mehta), she was much less discerning when it came to getting rid of items from the mountains of notebooks, manuscripts, research, bills, receipts, diaries and letters that she accumulated throughout her life.

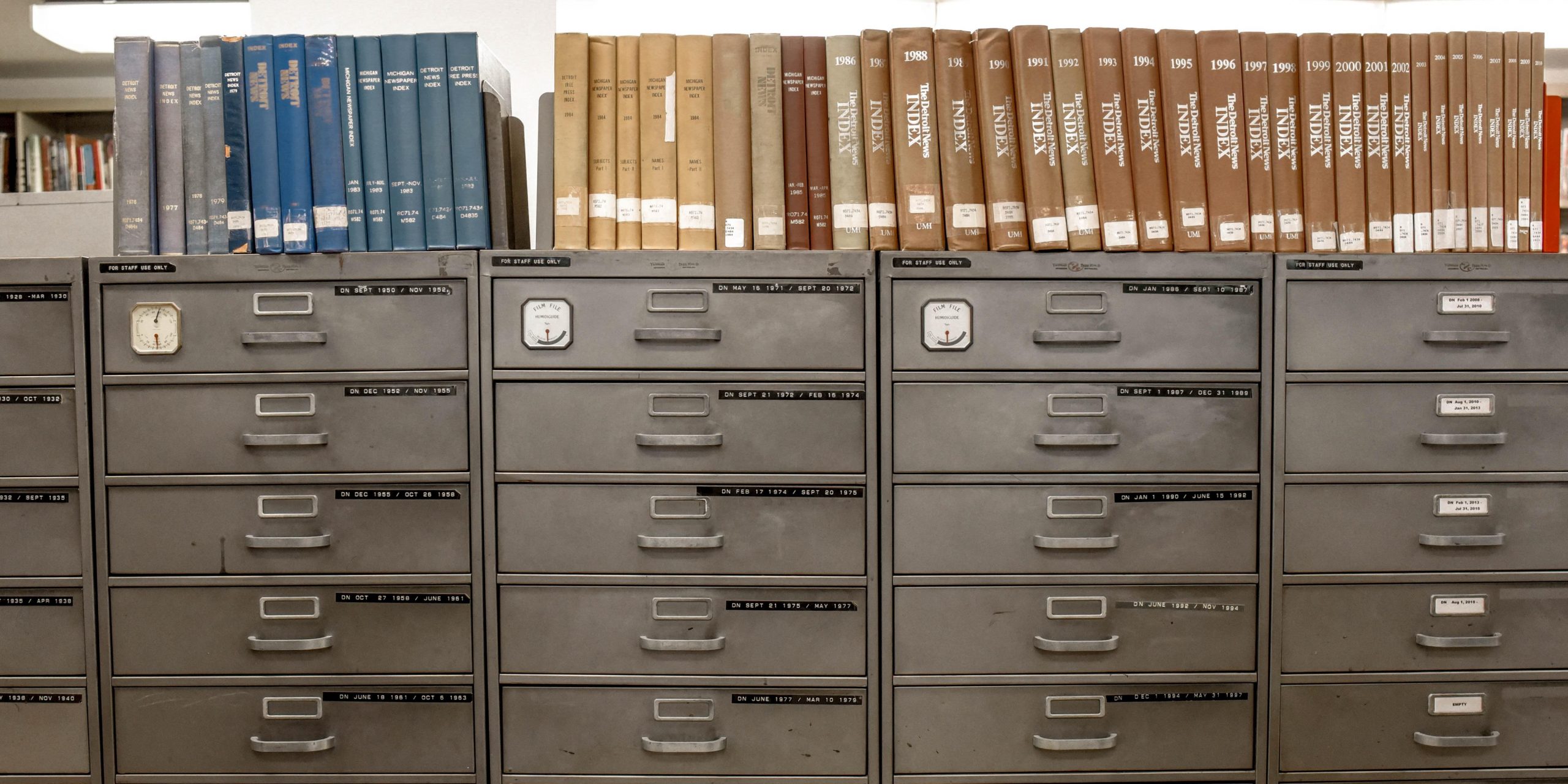

My book, Muriel Spark’s Early Fiction: Literary Subversion and Experiments with Form, is the first non-biographical study to draw extensively upon Spark’s two vast archives of personal correspondence, research materials, manuscripts and notebooks, which are held at the National Library of Scotland in Edinburgh and the McFarlin Library at the University of Tulsa. Broadly speaking, the Edinburgh and Tulsa archives present two very different versions of the author, with the contents of the former revealing more about Spark’s personal and professional life, and the materials in the latter relating to the research and writing of her novels, short stories, poetry and plays. Whereas the National Library of Scotland teems with contracts, receipts (spanning everything from Spark’s acquisition of a racehorse from the stables of Queen Elizabeth II to innumerable bills from her hairdressers), cheque stubs, appointment diaries and postcards, for example, the notebooks and research folders that fill the McFarlin Library offer a much more revealing insight into her fiction, and have thus been of far greater use to my research.

Perhaps surprisingly, my book rarely refers to the manuscripts of Spark’s novels and focuses instead on their corresponding notes and research materials. This is due to the uncanny, near-perfect resemblance that these manuscripts bear to their published counterparts, thus revealing very little about their own composition. A scholar consulting the manuscript of The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie, for example, will struggle to spot any significant differences between the words neatly handwritten on alternate lines of one of Spark’s large, spiral-bound notebooks (always procured from the Edinburgh stationer, James Thin, no matter where in the world she was living) and those printed on the pages of the published text. ‘I don’t correct or rewrite,’ Spark remarked of her novel-writing process in a profile piece for The New Yorker, ‘because I do all the correcting before I begin, getting it in my mind. And then when I pounce, I pounce’. To ‘pounce’ with a perfect landing, it was essential for Spark to compile what she described as ‘a bundle of notes’ beforehand, to which she could refer while writing her novel:

I need a sheet [of notes] for every character: what they say, what they wear, who knows what, who knows whom, and what they do – all cross-referenced. I have a place for everything that wriggles – human beings, dogs, ice cream. Then I can fit it all together.

It is to these various ‘bundle[s] of notes,’ contained for the most part in the McFarlin Library, that I return throughout my book. In doing so, I tend to discuss what Spark chose either to omit from, or further develop in, the largely uncorrected manuscripts of her novels. Among these materials is a paragraph-long fragment entitled ‘The Parquet Floor,’ from which the full manuscript of Spark’s 1968 novel, The Public Image, can be seen to have emerged. I look, too, at dialogue drafted for (yet, significantly, never used in) The Driver’s Seat, as well as the numerous plot sketches which Spark’s explicitly metafictional debut novel, The Comforters, would conjoin into a tangled skein of competing fictions.

There are, however, some notable exceptions. My heart stopped when, flicking through Spark’s notes for The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie, I noticed a draft of an unpublished short story. ‘The Way Up’, the story’s original title, is crossed out in favour of the far more Sparkian ‘A Dangerous Situation on the Stairs’ (I imagined Spark taking a withering glance at that first title and sighing: ‘no, that implies nowhere near enough peril. This one, on the other hand…’). Over three brittle, brilliant pages, the story narrates an increasingly claustrophobic romance between two middle-aged lovers. As the seasons change and leaves pile up outside the door, the couple settle into an increasingly restrictive charade of romance, with the woman feeling compelled to play-act a subservient role. This type of ‘Dangerous Situation’ crops up throughout Spark’s work, and it’s fascinating to see it drawn in stark miniature here.

There remain countless things to be said of both archives. More demands to be written of Spark’s correspondence with contemporaries including Christine Brooke-Rose, Iris Murdoch and Doris Lessing, for example. A whole book, meanwhile, could be written about her well-documented efforts to have her works adapted for stage, screen, radio and even opera. But that’s a job for another Sparkivist. Whoever they are, they’ll need stamina.

About the Book

This book presents a detailed critical analysis of a period of significant formal and thematic innovation in Muriel Spark’s literary career. As the first critical study to draw extensively on Spark’s vast archives of correspondence, manuscripts and research, it provides a unique insight into the social contexts and personal concerns that dictated her fiction.

Dr James Bailey is Honorary Research Fellow in English Literature at the University of Sheffield. He is the author of Muriel Spark’s Early Fiction: Literary Subversion and Experiments with Form (Edinburgh University Press, 2021) and co-editor, with Emma Young, of British Women Short Story Writers: The New Woman to Now (Edinburgh University Press, 2016). He now works for Arts Council England.