By Namatullah Kadrie

The COVID-19 pandemic is only the latest of many public health crises that have struck Afghanistan—and that have made the country a site of international intervention by medical experts. Indeed, it was the fifth international cholera epidemic of 1881 to 1896 that brought an English woman, Lillias Hamilton, to the court of the Afghan king, Amir ‘Abd al-Rahman Khan.

Lillias Anna Hamilton, who was born to Scottish parents in New South Wales, Australia, but moved to Cheltenham, UK, was a pioneer woman doctor who travelled to India and opened a private clinic. Thereafter, Hamilton fell victim to the cholera epidemic, acquiring the disease in Calcutta. The sickness disrupted her health to such an extent that the doctor was forced to temporarily give up her profession and seek a place for convalescence. She had heard much about the air of Kabul being conducive to health.

Coincidently, about the same time, Amir ‘Abd al-Rahman Khan was seeking a European woman who could familiarise the ladies of his harem with Western ways. Hamilton accepted the six-month stint partly because the money offered in exchange for her service was handsome enough to pay off the debts she had accumulated while indisposed in Calcutta. Five months into her contract, Hamilton was offered a position as personal and court physician to ‘Abd al-Rahman Khan—an appointment she accepted reluctantly.

Hamilton was in the right place at the right time. Not only would she prove to be an important eye witness to the Amir’s tyrannical rule and exploitation of Islam, but also an indispensable health care provider from 1894 to 1897.

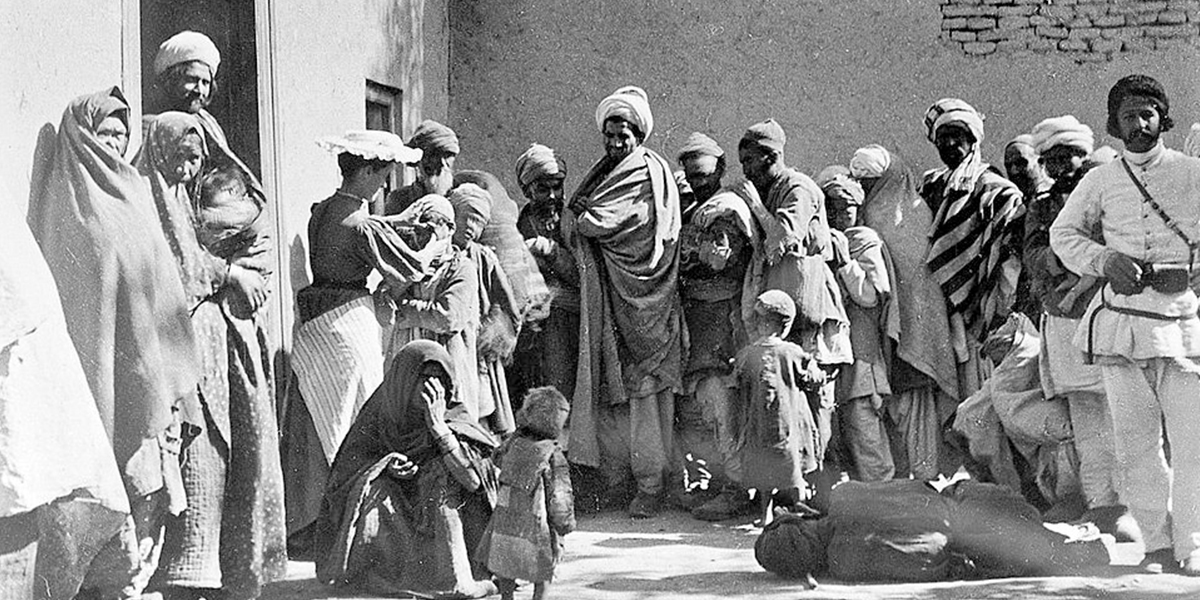

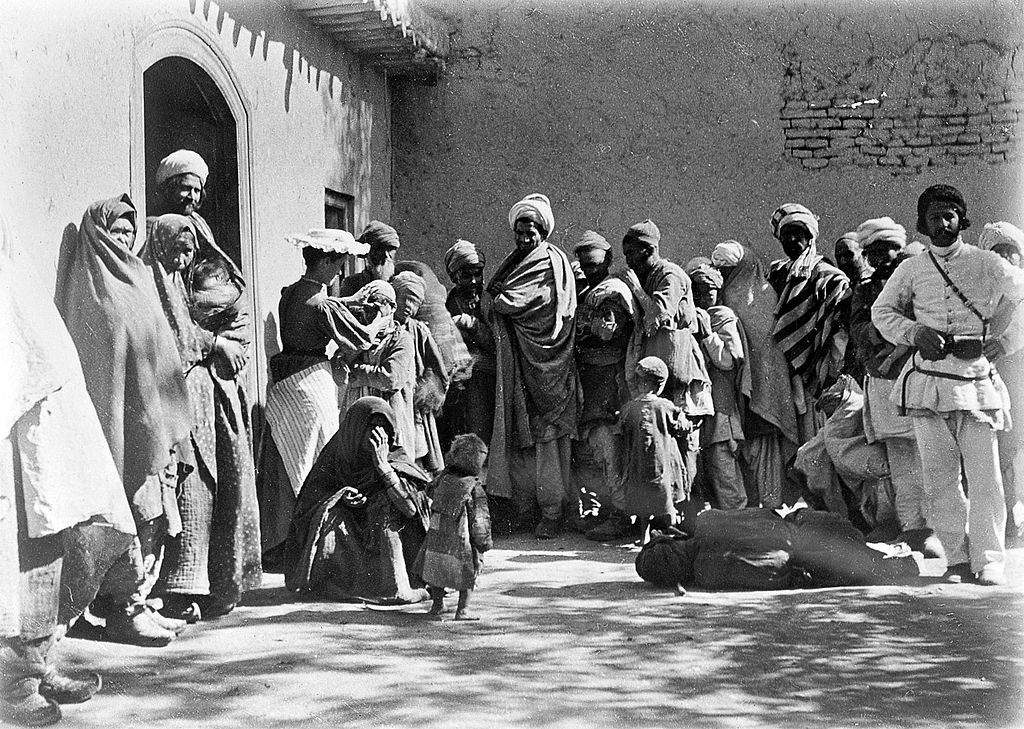

Although obliged to offer medical service to the despotic Amir, his household, and his high officials, Hamilton did not limit her medical service and expertise to the royals and the aristocrats. Rather, she directed all her spare time to treating the ordinary citizens of Afghanistan. With the assistance of her servants, she estimated that she treated as many as 750 people a day for all sorts of health issues and complications.

Credit: Wellcome Collection CC BY

Hearing of the new European doctor in town, Afghans in Kabul would queue up in front of her tent in Bagh-i Babur to receive medical advice and treatment. Later, Hamilton established a small clinic in Kabul to receive patients there. Whereas now tuberculosis, malaria, and more recently COVID-19, poses a major public health challenge, during the late 19th-century, it was cholera, smallpox, and cataracts that afflicted so many Afghans. Although unable to find a treatment for cholera, Hamilton did introduce vaccination for smallpox, effectively becoming the first person to do so in the country’s history. She claimed to have substantially reduced the smallpox endemic through variolation.

Credit: Wellcome Collection CC BY

It would be many decades later before the work begun by Hamilton would be taken up by the Afghan government and international NGOs. In the late 1960s, a collaboration between the World Health Organisation, the Afghan Ministry of Health (MOH), and an all-female team from the U.S. Peace Corps, sought to eliminate the disease through vaccinations as part of the WHO’s Smallpox Eradication Programme. In a span of three years, Peace Corps volunteers were able to vaccinate some 80 percent of the population. On May 8, 1980 WHO officially declared the world free of smallpox. Both Dr Hamilton and the Peace Corps had played important roles in its eradication in Afghanistan, albeit at different times. However, despite the eradication of smallpox in Afghanistan and around the world, other diseases which are just as challenging, have emerged—the latest being the Coronavirus. With over 7,000 confirmed cases of Coronavirus patients in Afghanistan and 173 known deaths as of May 18, 2020, many fear that the country, beleaguered by four decades of war, faces a “perfect storm of hunger, disease and death.”

The recent attack on a maternity ward demonstrates another layer of difficulty to the challenges of health service provision. On Tuesday May 12, 2020, gunmen disguised as police stormed a Medecins Sans Frontier–run maternity war in Dashti Barchi in a predominantly Hazara neighbourhood in the west of Kabul, killing 24 people, including two newborn babies. The terrorist attack, which according to the Afghan Government was carried out by the Taliban, was not the first time MSF came under attack. Five years earlier, MSF’s trauma centre in Kunduz came under attack by an American gunship, leaving 14 staff, 24 patients, and four caretakers dead, and eventually leading to the closure of the facility.

While the nascent experimental Coronavirus vaccination shows promising signs, and the political stalemate over presidency in Afghanistan appears to have subsided, it remains to be seen whether a global effort can eradicate a new disease once again.

Afghanistan is a refereed journal published twice a year in April and October. It covers all subjects in the humanities including history, art, archaeology, architecture, geography, numismatics, literature, religion, social sciences and contemporary issues from the pre-Islamic and Islamic periods. Read Namatullah’s article from Volume 3, Issue 1, ‘“Pen and tongue” untied: Lillias Hamilton’s uncensored view of ‘Abd al-Rahman Khan‘. Find out how to subscribe to the journal, sign up for Table of Contents alerts, or recommend to your library.