Mark Quigley,University of Oregon

With commemorations of the 1918 Armistice this past November, four years of centennial reckonings with the First World War effectively came to a close. But just as the impacts of the war extended far beyond active hostilities, a series of less celebrated centenaries are just beginning to unfold that reveal how the war continued to ripple across a remarkably eventful decade. For Ireland and Britain especially, the ‘Great War’ transformed the bases of politics and the social movements that mediated the long-simmering conflict over Ireland’s place in the British empire. Indeed, as the autumn 2018 issue of Modernist Cultures explores, the experience of the war in Ireland is one of the more fascinating and least examined chapters in the cultural history of World War One.

Key changes wrought by the war can be discerned in the British parliamentary election of 14 December 1918. Coming scarcely more than a month after the Armistice, the election showed how the war had scrambled political alliances and identities for suffragists, Irish nationalists, Ulster unionists, and the major British parliamentary parties.

Watershed victory for women’s suffrage

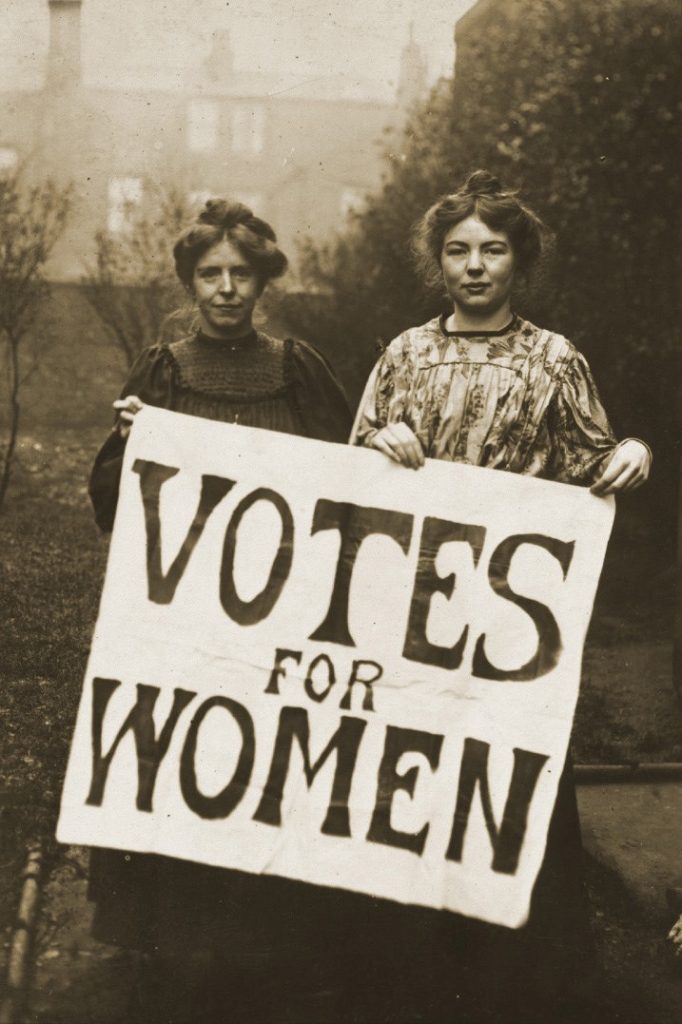

The most momentous result of the 1918 election was the victory of the first woman elected to the Westminster parliament, the Irish feminist radical Constance Markievicz, in the first election women exercised their new—yet still unequal—parliamentary franchise. The tremendous importance of this milestone for women’s suffrage, however, tends to obscure the divisions World War One produced in the suffrage movement.

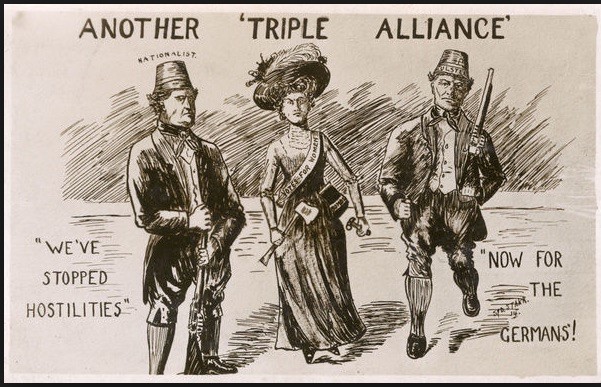

Prior to the war, the leading figures in the English suffragist movement, Emmeline and Christabel Pankhurst and their Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU) activists, had embarked on a campaign of radical disruption. This campaign led from heckling and breaking windows to arson, bombings, and a hatchet attack on the prime minister’s carriage. Suspending these efforts after the outbreak of the war, however, Emmeline and Christabel Pankhurst embraced the war effort, shunning colleagues who opposed the war and even changing the name of the WSPU newspaper from The Suffragette to Britannia.

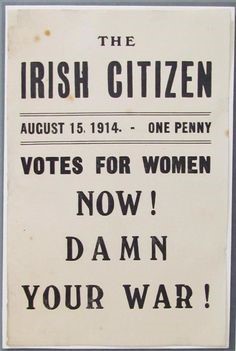

By contrast, leading Irish suffragists strongly opposed the war, famously proclaiming ‘Votes for Women Now! Damn Your War!’ in advertisements for the Irish suffrage paper, The Irish Citizen. Opposition to the war effort continued to grow amongst Irish suffragists. As a result, the First World War enabled the movement to build alliances with wider sections of the Irish public who had previously been suspicious of suffragism as an ‘English’ movement that treated Ireland with an imperious condescension and impeded Irish Home Rule. Irish suffragists’ split from English suffragism over the war thus proved instrumental to Markievicz’s election as the first female MP. Notably, Christabel Pankhurst lost in her own effort to win a seat in the 1918 election. Her alliance with the wartime prime minister David Lloyd George—whose house the WSPU had bombed before the war—failed to generate sufficient support beyond her core constituency.

Rise of the Tories

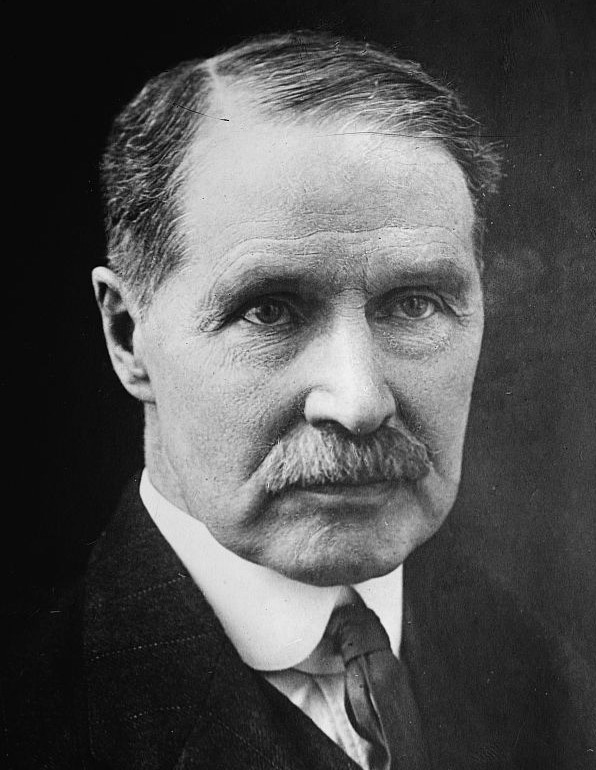

Lloyd George’s own victory in the 1918 election allowed him to continue as prime minister atop a splinter faction of the Liberal party that campaigned in coalition with the Conservatives led by Bonar Law. Law’s Tories were the overwhelming winners, however, with more than triple the seats won by the Lloyd George faction—enough for an outright majority. The war again played a crucial role in this seismic re-ordering of the British parliamentary parties with incompetent management of artillery shells leading to the Liberal government’s collapse during the war and the splintering of the party.

Consolidation of parliamentary support for Irish unionism

Pivoting to a post-war Conservative political dominance, Bonar Law’s electoral success also revealed how the war had reversed the fortunes of advocates for preserving the union between Ireland and Britain. Just before the war, the Irish Home Rule Bill had provoked an acute crisis. Amidst government threats to use force to impose Home Rule on resistant Ulster unionists, the specter of civil war loomed large in the summer of 1914. Bonar Law strongly supported Ulster unionists’ right to resist Home Rule by whatever means. As the Home Rule Bill was taken up for passage shortly after Britain entered the war, he led Conservative MPs out of the Commons in protest. With Home Rule suspended during the war, however, Law’s huge gains in 1918 meant Irish unionism emerged from the war with strong parliamentary support.

Eclipse of Home Rule

While meant to celebrate a united front in support of the British government that each group had previously opposed for different reasons, images such as these also undercut support for Redmond’s IPP and furthered a sense of division amongst leading English and Irish suffragists.

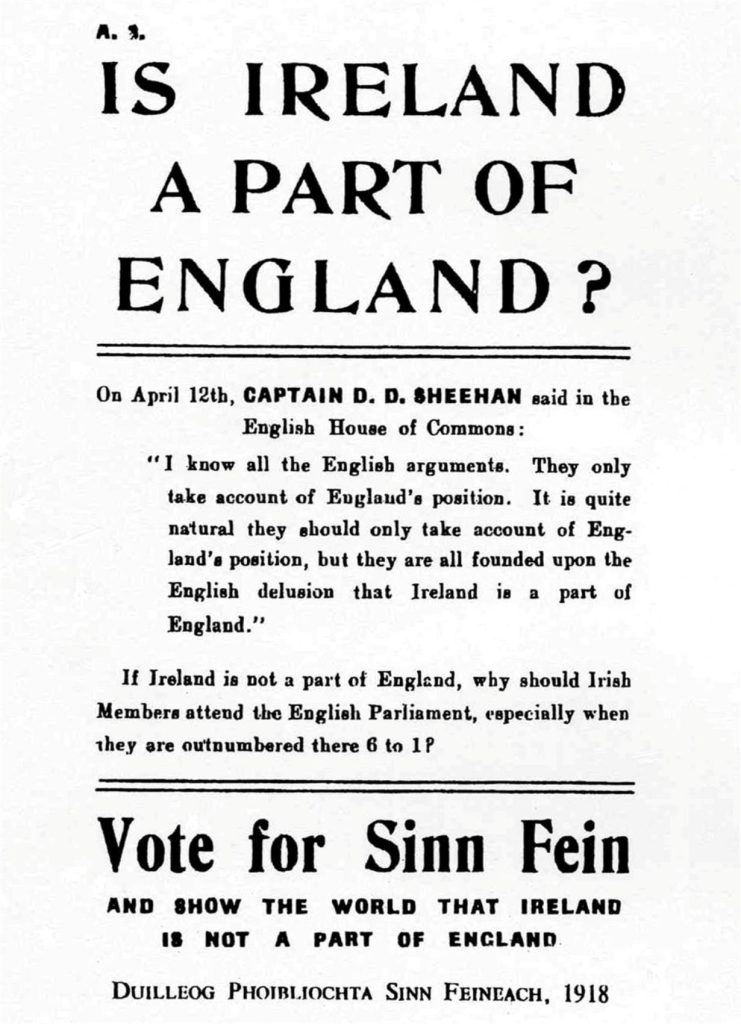

In Ireland, the war undercut the Home Rule movement and engendered support for a more radical nationalist separatism. Home Rule had long been driven by the Irish Parliamentary Party (IPP) who provided the coalition support to sustain the Liberal government as the war began. The IPP leader, John Redmond, strongly supported the war effort and actively recruited for the British military. As casualties mounted, however, Redmond’s recruiting efforts became a drag on his popularity in Ireland and provided an opening for more radical nationalists opposing the war. Sympathy for militant nationalism grew in Ireland after the execution of the leaders of the 1916 Easter Rising and amidst widespread opposition to the plan to introduce conscription in Ireland culminating in the spring 1918 Conscription Crisis.

The IPP was thus virtually wiped out in the 1918 election as Irish nationalist support swung to those running under the Sinn Féin banner on a programme of abstentionism whereby those elected would refuse to take their seats in Westminster. Abstentionism registered protest against British rule in Ireland while simultaneously using the post-war ballot to claim a democratic mandate for a separatist government. Sinn Féin candidates won about 70% of the seats from Irish constituencies with the IPP winning 5% of the seats and unionist parties claiming the remaining 25%.

A New War

Just over two months after the Armistice and in the opening days of the Versailles Peace Conference, the bulk of the successful Sinn Féin candidates not being detained by British authorities met in Dublin on 21 January 1919. This first meeting of Dáil Éireann, the Irish separatist parliament, claimed its mandate from the overwhelming return of abstentionist candidates in the 1918 election. That same day, nationalist militants ambushed an explosives shipment in Tipperary. That attack would come to be viewed as the beginning of a new phase of Irish nationalist militancy and the first shots of a new war for Irish independence.

Though the Irish War of Independence tends to be framed within a distinct historical narrative of Irish nationalism, its origins are deeply intertwined with the shifts brought about by World War One. Thus, if we attend carefully to the complex centenaries associated with the conflict over Irish independence, the ongoing struggle for women’s voting equality, and the Irish Civil War unfolding over the next few years, we can register distinct echoes of the First World War and trace how that earlier conflict continued to shape events long after the guns fell silent on 11 November 1918.