By Ondrej Beranek and Pavel Tupek

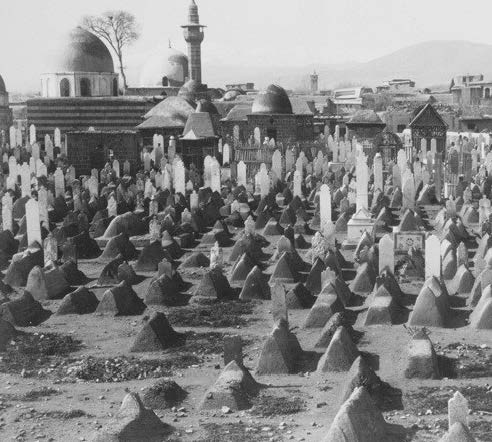

1) Over the past years and decades, various parts of the Islamic world – from Iraq, Syria, Mali and Tunisia, to Libya, Egypt, Saudi Arabia, Yemen and Bangladesh – have faced virulent attacks targeting Islamic funeral and sacral architecture. These attacks should not be viewed as random acts of vandalism, but as acts associated with ‘performing one’s religious duty’. The requirement to level graves (taswiyat al-qubūr), is attested in the Wahhabi–Salafi tradition and texts, and is quite often invoked by Saudi religious scholars and bodies. According to their belief, mosques, mausoleums and domes containing graves must be levelled to the ground, especially when they are used as places of worship. In the Salafi understanding, worshipping a human being, whether dead or alive, is a kind of polytheism (shirk) and, as such, is tantamount to idolatry. Even the mere fear of idolatry associated with graves, the so-called temptation to worship and venerate graves (fitnat al-qubūr), justifies their removal.

2) Views on graves in Sunni Islam – visiting them and the building of funerary structures over them – have undergone a long and complicated development process. In pre-Islamic times the cult of the dead was probably widespread, as was the practice of visiting the graves of ancestors, which were ascribed a solemn significance. With the emergence of Islam, however, a new trend, discrediting pagan rituals, emerged. Muhammad himself, if we are to believe the Islamic tradition, did not have clear-cut opinions regarding such issues. Later on, while the majority of the ulama did not broadly criticise all grave-related customs, a minority of scholars lectured otherwise.

3) The first concerted opposition to graves related practices emerged among Hanbali scholars, culminating in the pronouncements of Ibn Taymiyya, the foremost and still today the most widely quoted critic of ‘heretical’ practices in Sunni Islam. After that, it was the Wahhabi movement that picked up this line of thought. The movement emerged in eighteenth-century Najd, in the heart of the Arabian Peninsula. Ibn ʿAbd al-Wahhab’s foremost legacy consists in formulating the basic vision of a rotten society, ignorant of ‘proper’ religious rules, allowing the excommunication of those Muslims who were not true believers and monotheists, and demolishing anything with an idolatrous potential. The ideas of Muhammad ibn ʿAbd al-Wahhab were disseminated in the form of printed Wahhabi texts, appearing in other parts of the Muslim world, most notably in Egypt in the west and as far as India in the east, thus generating the subsequent growth of a trend later to be described as Salafi Islam. Significantly, these trends and the dissemination of associated ideas led to an ever-growing number of physical attacks on funeral architecture, best exemplified by the Wahhabi conquest of the Hijaz in the early 19th century. This trend was further solidified in the second half of the 20th century with the growth of pan-Islamism, propagated mostly by Saudi Arabia and its religious establishment.

4) A further boost to iconoclastic ideas has been provided by the Ahl al-hadith movement, especially the work of Muhammad Nasir al-Din al-Albani, who – through his critical re-evaluation of hadith, the strict prohibition of imagery in all its forms and his call for the purification of doctrine – has strongly influenced global Salafi discourse in relation to iconoclastic issues.

5) The destruction of religious sites (both funerary and non-funerary) is not of course exclusively symptomatic of Islam. History is replete with evidence of blatant destructive behaviour by winning parties and the destruction of cultural or religious artefacts belonging to an enemy people, in order to subjugate, dominate or terrorise them. Some of the most obvious examples include the Conquistadors’ annihilation of Aztec culture, the Nazi destruction of German synagogues, Stalin’s destruction of churches, China’s demolition of Tibet’s monasteries, or the destruction of both religious and non-religious monuments in Bosnia and Kosovo. The purpose of this destruction was always similar: to eradicate the opponents’ collective memory and identity. Another similar feature is the habit of changing the purpose of these religious sites. The conquering Nazis turned the old Sephardic synagogue in Sarajevo into a garage, and Islamic graveyards in the Balkans were often cleared for parks. Hundreds of Armenian churches and monasteries met the same destiny, while religious buildings were systematically turned to new agrarian uses in Central Asia under the Soviets or in Cambodia under Pol Pot and the Khmer Rouge. ISIS did exactly the same.

6) ISIS frequently used, quoted, referred to, paraphrased or re-published both older Wahhabi–Salafi texts and its own productions. Shortly after ISIS took control of Mosul, in June 2014, it started to brutally assault both the living and the dead. According to verified databases, ISIS has destroyed almost 50 architectural sights in Mosul, including the entire group of unique 12th–13th century buildings. (The destruction is currently the subject of documentation of a team at the Oriental Institute of the Czech Academy of Sciences and its project ‘Monuments of Mosul in Danger’.)

7) Certain Islamic movements, most specifically Salafism, both in its broader meaning and its narrow interpretation as Wahhabism, try to control and uproot various local interpretations of Islam and annihilate religio-political opponents. Put simply, one of the main reasons behind the harsh approach towards cultural heritage is the fact that it has proved to be a very powerful instrument in the fight against rival ideologies, be they Islamic (Shii or Sunni) or even non-Islamic, such as Marxism, democracy and nationalism. In our book we argue that the strategic objective of iconoclastic acts, perceived as a religious duty, is to destroy the culture, background and pride of local people and their intellectual bedrock (power centres, shrines and cemeteries) and then build new ones (mosques and institutes) in the ‘Salafi’ style. We are nowadays witnessing a process of the monopolisation of Islam through Salafi scripturalism and reductionism, which undermines the basis of a centuries-old cult of the saints and replaces beliefs and practices associated with mysticism with formalised purism.

Ondřej Beránek is director of the Oriental Institute of the Czech Academy of Sciences.

Pavel Ťupek is lecturer in classical and modern Islam at the Institute of Middle Eastern and African Studies, Charles University, Prague.